#9 'I still haven't decided what I am'

I'm writing this at breakneck speed. I've a whole page of pieces I have to get to work on but on a grey Thursday morning, you, my darlings, take precedence

My Granny Toodles used to call everyone “my darling”. She wore bright turquoise and big rings and when we moved from South Africa to France in August, she came to stay for Christmas, and never went home. She is buried in Aix-en-Provence. I think of her every day because, I realise, I too call people “darling” and “dear” and I like that thread, don’t you? [NB - I posted this at lunchtime and now, over dinner, I’m reading Adrian Chiles, the man who writes about nothing, whose headline today, for a piece on terms of endearment, is really rather nice: “I’m happy to be called love, bab or even pet. But I’d travel miles to be someone’s duck”]

I woke up thinking about three things: A) that I’d told you it’s Frieze week but I was being a doofus to presume that everyone would know what that means — why should you?; 2) that artist Jan Hakon Erichsen recently told me he figured he’d need to do 100 videos before what he was doing started to make sense; and D)* that perspective is a really tough needle to thread, but a vital challenge to meet, if you’re to keep going, in any meaningful way.

A)

So, Frieze. It’s a dual commercial art fair, held in London’s Regent’s Park, since 2003, to which the world’s gallerists, art collectors, curators, VIPs, PRs and journalists flock for five days, and any members of the general public willing to part with a week’s wages PER DAY, for four. Seriously, to access both fairs today (Thursday, the first public day), you have to fork out £245. Just, like, no, right? The only way I’ve ever been is on a press pass or because a gallerist gave me a guest ticket. It is ludicrously exclusive. And with the VIP lounges inside this VIP tent on the VIP day, it just gets exclusiver, like nesting matryoshka dolls of only-us spaces.

But here’s the thing: I started Frieze festivities at the Jack Whitten show at Hauser and Wirth, which includes paintings in which Whitten, who was born in Alabama in 1939 and went on to become incredibly influential, mixed other substances with his paint partly because he couldn’t afford not to. One of the curators read out excerpts from his diaries wherein he repeatedly made mention of his lack of funds.

At one point, someone gives him some paint and he’s like, now I can finish my Whitney show: he was reaching career heights yet still struggling to make ends meet.

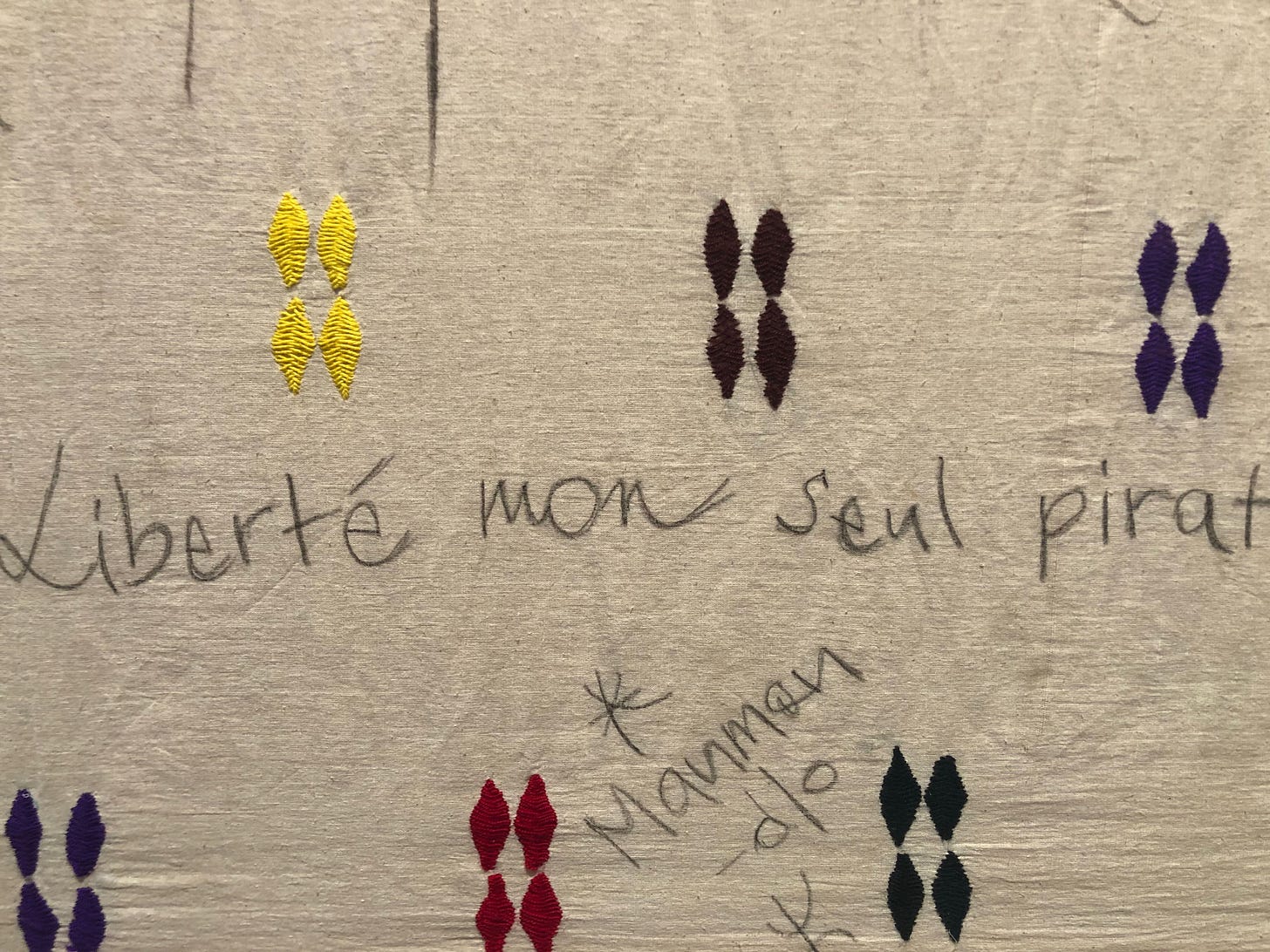

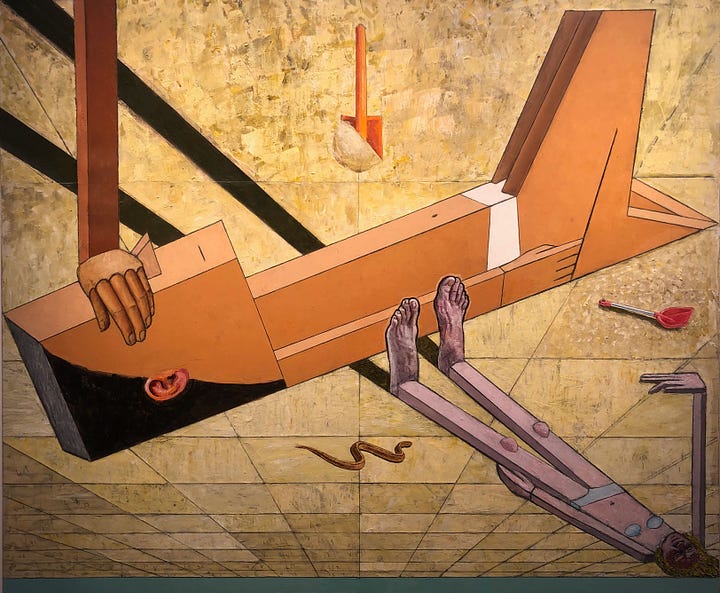

In front of the above collage — a beautiful piece — the curator explained that Whitten’s partner was a paper conservator, which meant he got access to different kinds of paper, hence the collage.

So many artists make work with so very little. And their economic situation is not self-inflicted but shared with lots and lots and lots of people outside of this kind of tent.

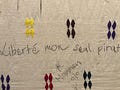

Anyway, here are some things I loved at Frieze London (fairs and galleries are inconsistent when it comes to caption info, so I don’t have everything): Malo Chapuy, “l’humble imagier”, Charwei Tsai’s inscribed shells, Kader Attia’s wounded terracotta, Guadalupe Maravilla’s devotional objects, Manjot Kaur’s miniatures, Théo Mercier’s rope and stone, Nengi Omuku’s works on Yoruba sanyan, Peter Uka’s stilling paintings, Jake Grewal’s lone print, Salman Toor (again! the joy!), Ashfika Rahman’s typological survey of televisions in the Bangladeshi wetlands, Noémie Goudal’s mathematical sculptures, Hamedine Kane’s embroidered spaces, Savannah Harris’s painted exuberance.

And that’s as far as I got before my phone died and I walked home. I’m going back tomorrow.

I actually went to Frieze Masters first. This newer of the two fairs is the OG’s moneyed aunt with the portered apartment on the Upper East Side. It has beautiful terracotta carpets and expensively greige walls and all the art history you can digest in five days, reminding you, with a jolt, if you work in art at all, why it is you love what you do.

Quite where history ends and now begins is a slippery thing. Many galleries are present in both fairs. Masters this year is notable for the many solo exhibits dedicated to legends who’re still working in their 80s and 90s (Frank Auerbach, Mernet Larsen, Isabella Ducrot) or who never got the full acclaim their work so clearly deserves before they passed (Anita Payró, Feliza Bursztyn, José Antonio da Silva) but carried on, regardless.

Elsewhere, a trio of unexpected Calders felt like splashing cold water on my face. A Joan Mitchell made me happy, as did this much awaited but unexpectedly tiny Manet (and frankly, all the better for it) at Hauser and Wirth. Sadanand Bakre’s Clown stopped both me and some random dude, who said “This is SO SEXY, ISN’T IT”, loudly, as he dived in front of me with his phone and apologised but continued bc my guy needed that pic.

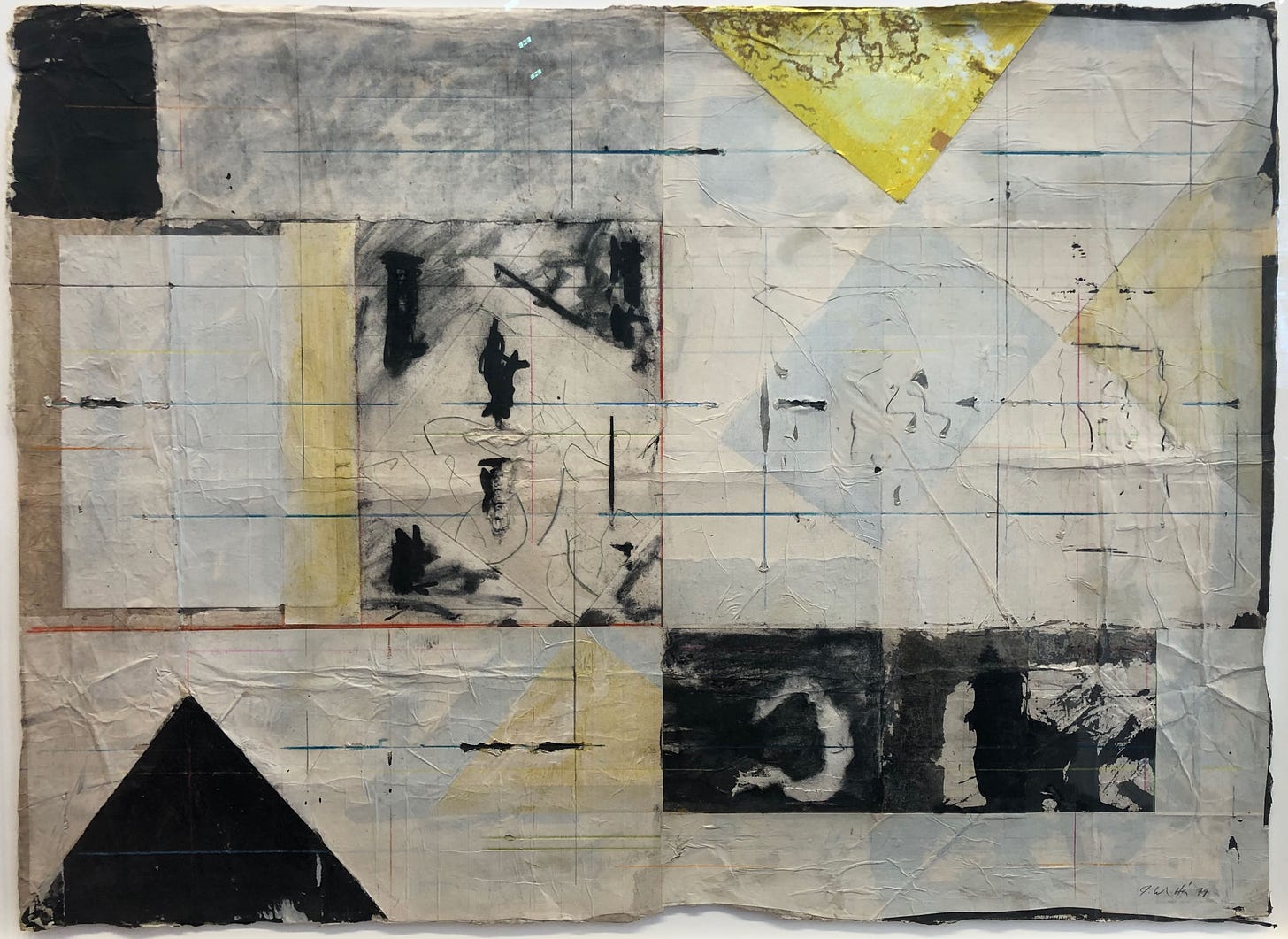

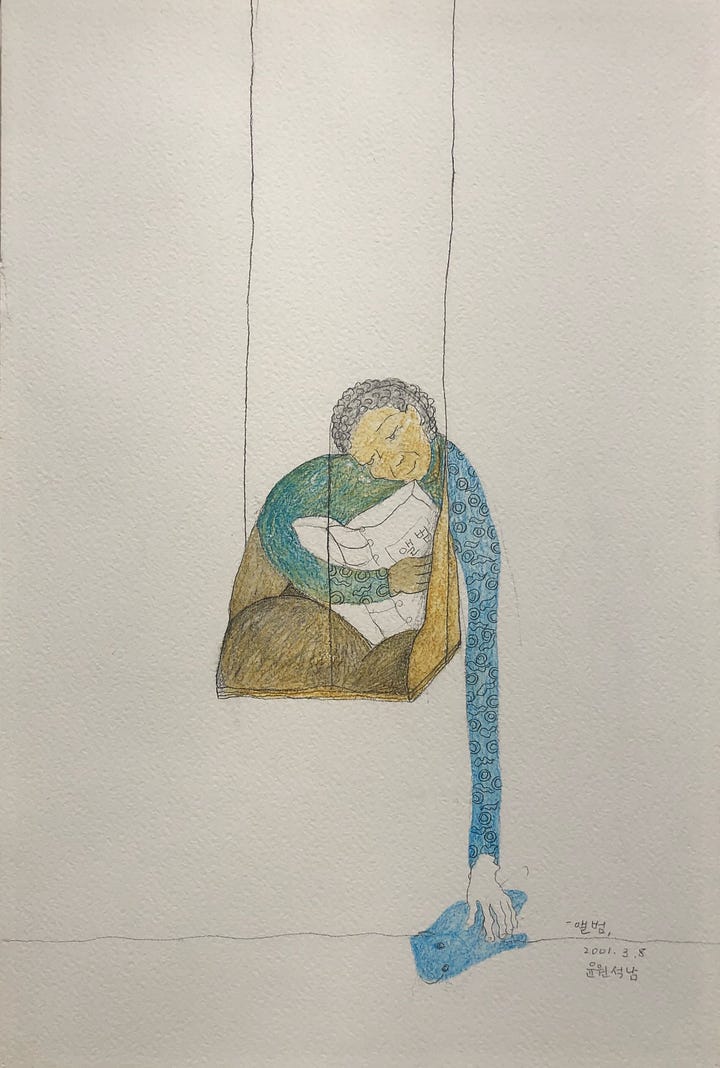

My favourite discovery was South Korean painter Yun Suknam: tender, intriguing drawings, paintings and painted wood bas-reliefs installed against a blue curtain in a way that told a whole story. I wanted to go for a long walk with her.

There were two magnificent Chaim Soutines and a set of Doris Salcedo pieces that almost brought me to tears, Soutine because his work always does, and Salcedo because of her bold, brutal, wounded austerity; some great Jackson Pollock drawings, and Nam Jun Paik’s frankly awesome handpainted Life is Drama tower from 1990.**

Then there was this tiny Dora Maar, quite possibly the smallest painting in the whole fair, just a hand-span in width. The fabled photographer and erstwhile Picasso sitter’s painting is so overlooked in art historical terms that this little landscape didn’t even have its own wall label. The gallerist pointed to the painting next to it and said, “Well, it’s the same info really: ‘Untitled (Landscape), circa 1960, oil on canvas’ but a bit smaller”. It had sold almost immediately, he said.

2)

Perseverance has sat on my shoulders all week, like an owl with claws and feathers both — and a head that can turn all way round, aware of too much even when it has its eyes closed. I’ve thought so much about Erichsen’s comment above, in part because I wonder, often, about the purpose of what I’m doing. Not just this writing but all of it. This week, in particular.

I sent out an early-week list of treats on Monday and I really hope you didn’t think it glib of me on a day like that. Some days, doing anything at all comes with a quite unmanageable sense of burden or fear or grief or anger and, often, a profound helplessness. No words really contain all that I mean, so the expression “these hard times”, in its bare-bonedness, just has to do. But then I think, if my sending you a few things about people striving to usher moments of beauty — or thoughtfulness — into the world brings you some measure of calm or joy, then I should keep at it.

Maybe 100 posts in, the work I do might start making clearer sense too.

The formidable curator Hans Ulrich Obrist has a new book out titled The Christo Interviews, which collates edited transcripts of all the conversations he had (this is a thing he routinely does, it’s properly amazing, the archive he’s amassing of artist interviews) with the artist famous for wrapping the Arc de Triomphe and the Reichstag. I’ll write more about this when I’ve finished reading it, but for now, I love this:

Christo was born in Bulgaria in 1935. While at art school, age 21, he fled the communist regime that had ruled his country for a decade and landed first in Austria, then Switzerland, France and finally the US.

In their first chat, HUO asks a very curator-like question: “When you started in the 50s, how did you connect to the early 20th-century avant-garde?” To which Christo replies, several minutes in, “I escaped to the West in my fourth year and although I have done very well, I still haven’t decided what I am.”

D)

Lastly, perspective. An art-fair flurry is nothing if not a crash course in perspective — if only because there’s precious little of it on display. It’s madness. It’s bonkers. I went to a press breakfast and watched grown people in expensive clothes rush an older barista and his one assistant, who clearly had not been briefed they’d have to serve this many people coffee IMMEDIATELY. The frenzy would have been startling if I hadn’t long archived other instances of art luvvies behaving like children high on sugar but with credit cards.

In the park, I walked past a woman combing — combing! — the long blonde hair with which her shoulder-bag was decorated. I mean, the clutch had hair, like, not just a fringe, but a full head of legit long hair that reached — because it was a shoulder bag — well down her thighs. And I overheard two drivers putting multiple Louis Vuitton bags into a car boot, the one saying to the other, “and I work with a lot of billionaires” and well, there that is.

Regent’s Park sits on Euston Road, the multilane traffic jam that circles central London proper. If you walk down it at day’s end, in particular, but actually, you can always see it if you look, there are people sleeping on cardboard, in tents, on mattresses or on the pavement itself, in staggering numbers. In January 2024 London councils reportedly put the number of homeless Londoners at one in 50: that’s 2% of the city’s population.

I’d started the week reading Darby English’s excellent if almost scarily scholarly How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness, in which the art historian writes about several Black American artists including Pope L. Pope L’s work never, ever looks away. I’m not sure there’s anyone who has made more powerful work than he grappling with what it is to be dispossessed. Nor is there a better analysis of that work’s power than English’s.

I don’t know how to hold in my hand both ends — or all these intervening points — on this insane spectrum of need v power. Art matters and it also can’t do shit. It matters so completely and not at all. Maybe that’s perspective, that questioning. That uncertainty. That honesty? Maybe it’s continually — not just once, but every day anew — deciding what it is that you are, what meaning you ascribe to what you do and why, and for whom it’s all for.

Pope L, on his Crawls: “When you do a performance you have to have some surface that tells people who you are. So I had to figure out, like, who was I? And I realised, I was going to work!”

Notes

**Also at Masters, a 4,500-year-old torso in marble (“possibly by the Copenhagen Master”) that also almost made me cry, so beautiful was it. And the “only royal Egyptian sarcophagus to ever be offered for sale on the art market” (it’s open which means you see the incredible 3,000 year old yellow and white stripes, replete with perfect rows of hieroglyphics, painted on the inside of the lower tray, as it were; but also, it’s been opened — I have many questions, not least whether Princess Sopdet-em-haawt oughtn’t be returned to her resting place).

World of echo

Walking as a state of mind

Christo famously didn’t have chairs in his studio. “I do not sit,” he says with more emphasis that most people, in the 2018 documentary, Walking on Water, “I do not sit!”

The project that film documents is The Floating Piers, the 3km of giant bright yellow temporary docks he and Jeanne-Claude installed on Lake Iseo in Italy for 16 days in 2016. Over 1.2 million people reportedly walked those straight lines between Sulzano, Monte Isola and the island of San Paolo. Afterwards he said that those who went “felt like they were walking on water—or perhaps the back of a whale".