INTERVIEW An Art Institute of Chicago curator on Pan-Africanism as a fruitful idea—and an aesthetic

The new Project a Black Planet exhibition looks at how a constellation of artists from all over the world have engaged with ideas of Black liberation

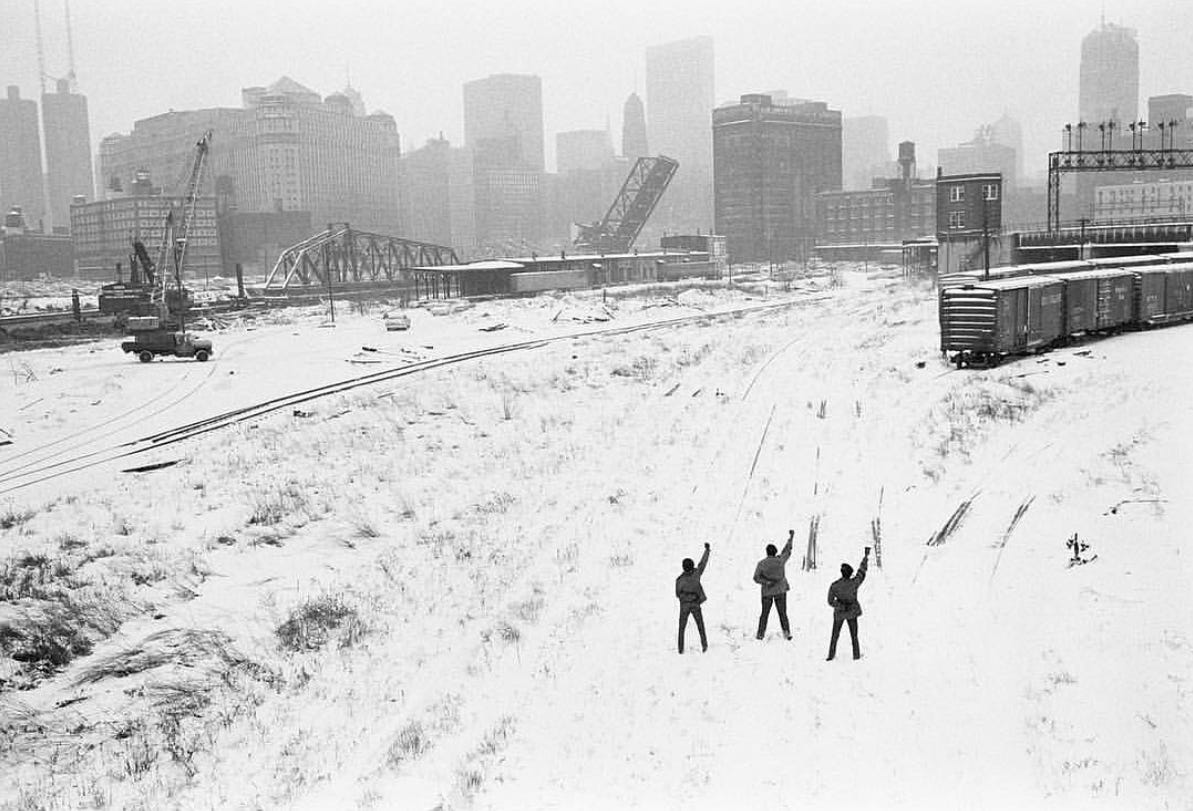

One of the most indelible images I know is Hiroji Kubota’s photograph of three Black Panther leaders give the power salute in the snow, in a downtown railroad.

Kubota was born in 1939 in Kanda, a neighbourhood of central Tokyo, and left Japan in the 1960s for the US. He got to Chicago, one of the birthplaces of the Black liberation movement and the so-called Capital of Black America, right as the Black Panthers were coming to the fore. Kubota made friends with many in the group. His photographs serve as an invaluable record of that time.

When I interviewed US photographer Mikael Owunna about this incredible shot of four women with snowflakes on their lashes, I immediately thought of Kubota’s image. Owunna’s four-fold portrait acts as a glorious grace-filled coda to Kubota’s fearless warriors.

Throughout 2024, I’ve been following from afar the Panafrica Across Chicago season. I mentioned before mural the UK's Otolith Group (Kodwo Eshun and Anjalika Sagar) unveiled at the Art Institute of Chicago in September. Titled A Massive Concentration of Black Interscalar Energy, this piece riffs on the films Senegalese directors Ousmane Sembène and Djibril Diop Mambéty made between 1963 and 2003. “Picture a mural,” says the rather beautifully written press blurb, “that montages the spaces, bodies, faces, forms, gestures, expressions, geometries, and geographies of the cinematic Sahel.”

This week marks the opening of the season’s final event, a sprawling survey, titled Project a Black Planet, that attempts to unpack how fertile the idea of Pan-Africanism has been for artists through the generations and across the globe. Featuring 350 objects that span a century from the 1920s to today, the show maps Panafrica “as a shifting and boundless constellation that transforms and reassembles standard representation of the planet”.

There are lots of actual maps and flags, installations, paintings and photography from the likes of Samuel Fosso, Tavares Strachan, Yto Barrada*, Chris Ofili, Zanele Muholi and David Hammons (here, you’ll see his African American Flag from 1990; I’m never not thinking about Hammons and snow too, with his Bliz-aard Ball Sale, from 1983).

See too, the wonderful Loïs Mailou Jones (below), a contemporary of the Harlem Renaissance movement. This glorious medley of works engages with and celebrates, as curator Antawan I Byrd puts it here below, Pan-Africanism’s “core principles of equity, freedom, and solidarity” in all kinds of ways.

For a preview for the Art Newspaper, I interviewed by email Byrd, who is an art historian and associate curator of Photography and Media at the Art Institute of Chicago. He has co-curated the show with his colleague Matthew S. Witkovsky, political scientist Adom Getachew and Elvira Dyangani Ose, the director of the Museu d’Art Contemporani in Barcelona.

Previews allow for very few words. But Byrd was too generous with his replies and so wonderfully interesting for me to just file away what he said. So here’s our full exchange, edited for length and clarity.

Dale Berning Sawa: The press materials highlight that this is the first exhibition to dig into Pan-Africanism's cultural manifestations but also that Pan-Africanism is yet to be fully examined as a worldview. Can you elaborate?

Antawan I. Byrd: Early on, my colleagues and I spent a great deal of time analysing how the term “Pan-Africanism” had been variously defined and used, from the late 19th century to the present, across both political and cultural contexts. It was a revelatory historiographic undertaking.

I was surprised to see how Pan-Africanism had been evoked through all kinds of phenomena, from broadcast media consortiums in West Africa and Black bookstores throughout the diaspora, to trade unions in the Caribbean, as well as regional political blocs and federations in and across these geographies.

Of course, there are the historic conferences and congresses that have evoked the term, as have the state-sponsored festivals in Africa such as FESMAN ’66 [the First World Festival of Black Arts held in Dakar in 1966] and FESTAC ’77 [the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture held in Lagos in 1977].

The term has further been used in numerous important exhibitions, sometimes in divergent ways or through related concepts such as Black Internationalism, Afro-Modernity, or Afropolitanism.

All of this activity, spanning more than a century, has resulted in a complex terrain wherein Pan-Africanism as an idea and an aesthetic (e.g., the colours of the Pan-African flag) has become familiar yet can also feel elusive. With the exhibition and its accompanying publication, we intend to survey and bring greater coherence to the concept’s influence on art and culture.

DBS: I like the dual meaning in the title, both "projection" (of a film or an imagined future) and "project" (a plan in progress) -- it suggests a push and pull between idealism and activism. Does that chime with what the show feels like? What does walking through the show feel like, for you?

AIB: This is spot on! There is a utopianism at the core of Pan-Africanism’s ambition for global unity, cooperation, and equity. Yet, as we know, utopian thinking can catalyse a range of creative activities and forms of activism.

The experience of the exhibition is such that visitors are called to shuttle between the ideal and the real. Some artworks and cultural forms are steeped in proposals for the future, whereas others narrate or reflect upon past historical events or figures. In nearly all of the sections, we adopt a non-linear approach to presenting objects and rely on the overall theme of the section to provide coherence.

In the Interiors section, for example, visitors encounter prison drawings made in 1965 by Malangatana Ngwenya while incarcerated in Maputo for his political activism. The drawings depict a lone, emaciated figure locked in a prison cell.

Nearby is an incredible painting by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Much-Maligned of May (2023) which, like much of her work, invites the viewer to contemplate the inner lives of the wholly imagined subjects she depicts. The work shows two subjects contemplating the sounds of a guitar.

The visitor is thus moved between the stark realities of political imprisonment during decolonisation in Mozambique and the sense of mental escape provided by music. At each turn in the exhibition, the visitor is invited to contemplate and make their own projections for the world they desire.

DBS: What are some of the most salient pieces in the show, for you?

AIB: Yto Barrada’s Tectonic Plate (2010) is one of the first works I had in mind as we began planning the show. There is a striking clarity about the work with its presentation of movable continental plates. Underlying its simplistic form is an empowering and everlasting invitation to imagine the world otherwise, whether in terms of immigration policies, climate fallout, or social relations, etc. The sculpture is a sort of projection machine fueled by the perspectives of people of colour, as suggested by Barrada’s choice to cast the continents in shades of epidermal brown. In this sense, the work is a fitting tribute to Pan-Africanism’s global reach.

Another work in the show that really moves me is Beauford Delaney’s Self-Portrait in a Paris Bath House (1971), which I saw midway through the planning of the show. Delaney never realised his desire to travel to Africa, but he made numerous works that reference the continent. Here he projects himself at the center of an Afrocentric worldview as registered by visual references to Egyptian hieroglyphs, Ashanti ceremonial thrones, and East African beadwork adornment. Delaney, who was Black and queer, is among several artists in the show whose work redresses a longstanding bias in histories of Pan-Africanism, namely the limited recognition of identities that exceed heteronormative ways of being.

DBS: Garveyism, Négritude and Quilombismo delineate a clearly global phenomenon, with the US, the French Caribbean and Brazil represented. How does the show dig into how these movements connect?

AIB: Early in the exhibition, we introduce Pan-Africanism and show how artists, activists, and communities have embraced its core principles of equity, freedom, and solidarity in diverse ways. We provide a baseline definition and then guide audiences through some of the ways Pan-Africanism has manifested through the example of three concrete historical movements: Garveyism, Négritude, and Quilombismo.

The history of each movement is presented through explanatory texts, and the objects displayed in each corresponding section provide various points of entry—across time and geography—into understanding underlying ideas.

In the Quilombismo section, for instance, we introduce the term’s origins in the Kimbundu language before defining it as a self-governing rebel territory founded by escaped enslaved people. We then explain how Brazilian artist Abdias do Nascimento used the concept to develop a philosophy of liberation. With these insights, the visitor is equipped to interpret and understand the artworks displayed in this section: works that incorporate imagery of "survival blankets," works of abstraction and coded language, as well as a work by Nascimento, coalesce to reflect and develop Quilombismo’s themes of self-governance and secession.

It’s our hope that after visitors have encountered these three movements, they will have a sufficient understanding of Pan-Africanism’s global reach as these movements—and the artworks presented in these sections—span Africa, Europe, North America, South America.

DBS: Marcus Garvey is such a central figure. How does Garveyism differ from Pan-Africanism?

AIB: We present Garveyism as an important strand of Pan-Africanism, rather than claiming a difference between them. After Marcus and Amy Ashwood Garvey founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association in 1914, the organisation introduced a number of radical proposals for redressing the legacies of enslavement and the effects of colonialism.

While advocacy for the return of African diasporic peoples to the continent was common in the 19th century, Garveyism took this ambition to a whole new level through its Back-to-Africa movement. The exhibition and publication present Garveyism as a global mass movement that took shape through a range of aesthetic practices.

For example, the show examines Marcus Garvey’s unique oratory style, showing how through speeches, he was able to gain a following. Meanwhile, we address visual and iconographic practices—from map-making, performance, pageantry, and publishing—that were not only historically important to Garveyism but also significant to understanding its legacy.

The exhibition does not take a hagiographic approach. Rather we aim to explain ideas and practices central to Garveyism, often through the work of artists unrelated to the movement. Ilana Yacine Harris-Babou’s satirical video, Reparation Hardware (2018), is a great example. This work parodies current consumer trends for restoring old furniture as a way of discussing deeper issues of nostalgia and repatriation that resonate with Garveyism.

DBS: Does the show also reference Frantz Fanon’s work?

AIB: Yes, Fanon’s work pervades the exhibition and is cited widely across the essays in the catalogue. We include editions of his publications, particularly first edition English and Arabic translations, in order to demonstrate how Fanon’s ideas circulated and became widely influential.

In sections on Négritude and Blackness, artworks that grapple with Fanonian theories of double consciousness and fractured self-perceptions are prominent as are works that evoke Fanon’s thinking about how race is visually signified as outlined in his theories on the “racial epidermal schema” in Black Skin, White Masks (1952).

DBS: Can you talk about the collection of archival materials at the heart of the show?

AIB: We have six large interconnecting vitrines housing more than 100 objects representing Pan-Africanism’s interface with print and popular cultures. In contrast to the show’s other sections, here visitors encounter a strictly chronological presentation. Some of the items, like leaflets, posters, and brochures, index efforts to promote specific Pan-African events such as cultural festivals. Others, like vinyl records, novels and magazines speak to Pan-Africanism’s popular appeal.

DBS: Were there specific triggers for the wider Pan-Africa Across Chicago season? What has the response been so far?

AIB: Chicago has played a vital role in both the emergence and endurance of Pan-Africanism. At the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, the city hosted the Congress on Africa, a seminal event in which a multiracial cohort of thinkers and activists debated the continent’s future in the wake of European colonisation.

During the mid-20th century, the Black Arts Movement in Chicago used culture to facilitate transnational forms of solidarity, especially through the efforts of figures like the artist Margaret Burroughs, who founded the South Side Community Art Center and the city’s DuSable Museum.

Given such histories, it was important for us to forge relationships and collaborations across the city with universities, alternative art spaces, and civic organisations to cross-promote activities and events that visitors can see during the weeklong slate of public programming we’re calling Panafrica Days. The response has been incredible, there’s much enthusiasm all around.

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica is at the Art Institute of Chicago from 15 December, 2024–30 March, 2025.

Notes

*In 2018 I interviewed Barrada about a photograph she once took inside a prawn processing plant in Morocco. At the time she was building a public garden in Tangier, filled with all the plants used for dyes throughout history. That project has morphed into a full blown research centre and artist community called The Mothership, which finally opened last year: she explains more here. Planting. You see. It’s always about nurturing better things.

World of echo

When I interviewed British sculptor Dominique White in July, she told me she listens to music all the time. On her studio playlist, there's a little bit of Sun Ra, a little bit of Alice Coltrane, always Busta Rhymes, very specific techno. She baulks at the elitist part of the art world, where it's made for the few and not the many. "That's why I talk about music, because it's a very accessible way into Afrofuturism, or Afro pessimism, Black nihilism, celebrationism—there's always someone who, at some point has, basically engaged with that theory."

I started making a list of related tracks and musical thoughts for you to peruse but it’s become a whole post of its own, so look out for that tomorrow. It all starts with this life-changing tune: