#15 'When the eyes are shut, they are extraordinarily open'

On quicksands and saplings, snowflakes and sycamores, mackerel skies and mulberry fields — and Park Jiha's new album, All Living Things

On an autumn afternoon in 1895, the British geographer Vaughan Cornish stood on a Devonshire cliff path overlooking the English Channel and watched the waves coming in at low tide. He noted little waves glide over flat sands and long waves be rejected at an angle by a sand bank. “And as I watched, I thought,” he wrote afterwards, “what a fine thing it would be if the study of all kinds of waves could be coordinated.” Coordinate he did.

Cornish decided his field of enquiry should be called kumatology (!)* and his life’s work was from thereon, as Kevin Dann puts it in this excellent piece, “organized around the wave”. “Liberated from the need to work by his wife Ellen’s inheritance [!!!], the couple traveled around the world studying Earth’s variegated waveforms.”

When Ellen died in 1913, Cornish wrote a book for her, titled The Travels of Ellen Cornish. Being the Memoir of a Pilgrim of Science. And the following year, he published Waves of Sand and Snow and the Eddies Which Make Them, a beautiful poem of a geographical study, which he dedicated to his mother, Anne Charlotte Cornish, “who taught me as a boy to observe and reverence the creation.” Dann writes:

Travels opens with a lengthy description of waves in the Bay of Biscay, passes on to note wave patterns in the pools of Buddhist temples in Kobe, and then goes into exhaustive detail about standing waves in the various cataracts of Niagara Falls. Along with learning about barchan dunes in the Arabian Desert, snow mushrooms in British Columbia’s alpine forests, and cahots (undulations produced by sledges) in Quebec farm fields, Cornish’s curiosity leads him to make discoveries about the waves created by a London omnibus and by leaves blown against stone steps in Kensington Gardens. Part III of Waves of Sand and Snow finds parallel forms in deltas, quicksand, and mackerel skies.

Reverence—to honour and admire profoundly and respectfully—isn’t that commonly used as a verb, is it? I like how Anne Charlotte’s teaching echoes author William Martin’s entreaty to not ask your kids to strive for extraordinary lives but instead to help them “find the wonder and the marvel of an ordinary life”. “Make the ordinary come alive for them,” he writes. “The extraordinary will take care of itself.”

Both of which sentiments are actually about giving a kid—and yourself—time, aren’t they, and safety. About finding/affording/protecting enough time and space to let your eyes settle and your ears open, your senses come alive to the world around you.

Of course, to do so is to also risk your heart breaking. I can’t imagine that anyone attempting to knit their lives back together in LA or Tibet or Valencia or Noto or Aceh is looking at nature as a gentle healing thing right now. Or at the very least, they must be holding both its beauty and its terror with both hands, a giant unknowable thing, like Giacometti’s Invisible Object. We live at the mercy of a world that feels irreparably broken. But somehow, to live is also to repair? How?

Cornish’s study of waves covered water, sand, snow, sound—and the earth itself. At the turn of the century, he and Ellen witnessed firsthand the 1907 Kingston earthquake, which wrested the Jamaican capital from its roots, mid-afternoon, on 14 January. The quake and subsequent fire caused £2,000,000 in damages and overwhelmed the hospitals. Survivors camped out on the race course. A daily gazette published the names of the dead, who numbered over 1,200—2.5% of the population at the time—even as the city ran out of coffins. “It will be weeks and perhaps months before the story can be told in detail of the almost complete destruction of Kingston by earthquake and by fire on the afternoon of Monday 14th instant,” the Gleaner reported. “It is a fearful story and never be amply told.”

That fearful, untold story has nonetheless been repeated, again and again and again. There are some images in this account of the 2009 Marysville bushfire that I can never get out of my head: the person sheltering in a lake and having to duck underwater as the flames shot across the water in a single sheet. It is incomprehensible. So too, this most recent account of the flash flooding in Nova Scotia, from Tera Sisco, an inhabitant of West Hants whose six-year-old son Colton, died: “While [Chris, Colton’s father] was on the phone with 911, the house started to crack like a tree coming down. It was the water pushing against the house.” Tera says she knew early on something wasn’t right: “All day long, it had thundered. I love thunder and lightning storms or I should say: I loved them.”

Our hearts also break because sometimes people do really stupid things to those natural treasures that can yet be broken by hand. When Storm Agnes battered Britain in September 2023, the country emerged one precious tree short. The Sycamore Gap tree, a picture-perfect specimen that had stood 49ft (14.9 metres) tall, in a dip near Hadrian’s Wall, for 150 years and anchored a million marriage proposals, had been felled. It wasn’t the wind’s doing. Two men in their 30s were arrested, charged with chopping it down. They were released on bail, their trial date to be set later this month. No one can understand it. As one arboreal expert recently put it, “The tree meant so much to so many. Its destruction felt utterly senseless.”

The National Trust has grown 49 saplings (one for each foot of the tree’s height) from its seedlings. Nearly 500 charities and groups around the country applied to be custodians of one of those tiny sycamores. “They were from all walks of life,” one judge told the Guardian, “from pretty English villages to prisons. Everyone had their individual story and honestly, I could only read so many at a time. It was really emotional. They were all deserving. It was really, really hard to choose.”

The trust has called the saplings Trees of Hope. My instinct is to say, but what tree doesn’t give you hope? What tree or crest or snowdrift doesn’t help a bit? Then again, I’ve not had to face a wave 30 metres tall, or tried to outrun wild flame. Maybe when you have, the beauty of an ocean or a fire is died? And still, I think, living after that, any tiny thing—a bud, a shoot—it would still be something, no? It would have to be.

Here, then, a collection of beautiful somethings I’ve kept in my pocket for you this week:

All Living Things, Korean composer Park Jiha’s new solo album (14 February), a beautiful weaving of long slow sounds, played on the yanggeum (hammered dulcimer), the saenghwang (mouth organ), and the piri (bamboo oboe). Park deftly, patiently, scaffolds nine multi-strand melodies that take their time, each adding to the former like so many silk threads on a jacquard loom, drawing a landscape ancient and indelible. Opener, First Buds, lays out a warp of a short single notes in spacious groups of five, through which a weft of much longer, more floating notes meander, as loose and atmospheric as daybreak. Bloom, the third track and my favourite, announces itself a kind of courtly dance, with a pulsing reed-based rhythm embellished with interlocking melodies in chime and flute. Elsewhere Park uses glockenspiel, bells and her own voice. Her titles take you from the dark of wet earth to the green of first leaf and the flutter of autumn leaves up up up into the seasons’ cycles and the heavens beyond. This is not pretty music but something closer to river water on river rocks, so cold it burns your toes, so relentless it’ll cause you to lose your footing even when shallow, so clear it takes your breath away. It’s mountain air, dark in a crevasse, biting on a ridge, gentle when the sun walks down to meet you. It’s an insistent living portrait, in rhizome and sediment.**

These most exquisite shots of visitors in hanboks of lilac, claret and cerulean, walking through the grounds of Seoul’s 14th-century Gyeongbokgung Palace after that snowstorm in November.

Berlin-based photographer Jens Liebchen’s series of Japanese pines in the snow (currently on view at the Chaumont-photo-sur-Loire photography festival, until 23 February, Domaine de Chaumont-sur-Loire).

Marisa Merz’s performative beach piece, Coperte, and Mario Merz’s Fregene, documentation of which you can see in the Arte Povera show at the Bourse de Commerce in Paris (until 20 January). For these performances, Marisa Merz rolled blankets up with copper wire into long floppy things, like outsized draft excluders, and Mario carried them on his back to the water’s edge. But of course, not even cliff faces tame waves. The artist looks so small, the gesture, if it stops the water for a second, so futile, like any attempt to hold back a flood with your fingers. I love Marisa Merz saying: “When the eyes are shut, they are extraordinarily open.”

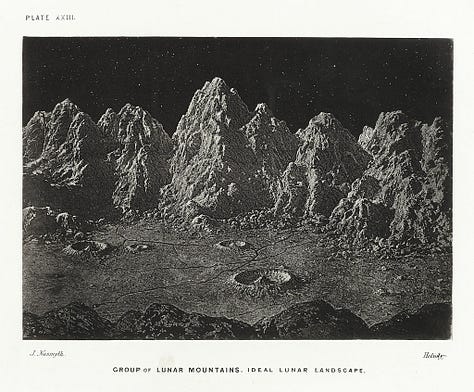

Marisa Merz, Coperte, 1968; Mario Merz, Fregene, 1970. Scottish astronomer James Nasmyth’s observations of the moon from 1874 — drawings he made by looking through his own telescope and paying very careful attention. He then made models from his drawings.

I particularly love that third pairing, the caption of which reads:

“BACK OF HAND & SHRIVELLED APPLE.TO ILLUSTRATE THE ORIGIN OF CERTAIN MOUNTAIN RANGES

BY SHRINKAGE OF THE GLOBE.”

James Nasmyth, The Moon, 1874. A new biography by John Bleasdale, about an all-time favourite director: The Magic Hours: The Films and Hidden Life of Terrence Malick. Man, Days of Heaven, that film. The locusts, the fire, the golden light, the music. It’s almost too much.

I love this from the NYer’s Richard Brody’s review: “Malick had been a colossal in-betweener, a master of many skills. He was lured in by the art that takes the most from the most. Entering the world of movies, Malick developed methods of his own in order to create experimental films—not in the conventional sense of avowedly avant-garde non-narrative but in the scientific sense. From the start of his career, Malick filmed not to show but to see, to discover.”

Lê Phô, Mai-Thu, Vu Cao Dam: Pioneers of modern Vietnamese art in France at Musée Cernuschi in Paris (until 9 March). The show brings together 150 works by three graduates of the École des beaux-arts in Hanoï, who worked in France from 1937. I’m so sad to miss this, especially since many pieces are in private collections.

Details of: Mai-Thu, La Source. Vanves, 1966 (Private collection; photograph: Ana Drittanti); Vu Cao Dam, Famille. Vence, 1957 (Private collection; photograph: Michel Graniou); Lê Phô, Femmes au jardin. Paris, 1969. (Private collection). All images copyright: Adagp Flowers and poetry unite the three artists, with The Tale of Kiều, a foundational text and particular reference. Without knowing anything about Vietnamese literature, I do love the way Vuong Thanh words this bit of the prologue in his 2022 English translation of the epic poem:

Within a hundred-year lifespan in this earthly world,

Genius and Destiny have a tendency to oppose each other.

A turbulent mulberry-field-covered-by-sea period had passed.

The things that we saw still deeply pain our hearts.

It’s not strange that beauty may beget misery.

The jealous gods tend to heap spites on rosy-cheeked beauties.

“A turbulent mulberry-field-covered-by-sea period had passed.” How good is that?

I’ll leave you with Eliot, in Four Quartets, “between two waves of the sea”, a brief reprieve, a sapling, a knot, a promise:

We shall not cease from exploration And the end of all our exploring Will be to arrive where we started And know the place for the first time. Through the unknown, remembered gate When the last of earth left to discover Is that which was the beginning; At the source of the longest river The voice of the hidden waterfall And the children in the apple-tree Not known, because not looked for But heard, half-heard, in the stillness Between two waves of the sea. Quick now, here, now, always— A condition of complete simplicity (Costing not less than everything) And all shall be well and All manner of thing shall be well When the tongues of flames are in-folded Into the crowned knot of fire And the fire and the rose are one.

Notes

*Kumatology. A kumatologist! You’ve got to bemoan the fact that that nomenclature didn’t catch on. Though I will say it is a bit too close to “akumatize” for my ears. Akumatization is the daft method by which the villain in Miraculous Ladybug creates each episode’s supervillain. Of all the kids TV I’ve watched, this French number is the worst, its so ugly and leadenly formulaic. But sometimes knowing exactly what is going to happen is what a tired person needs I guess, so the littles loved it. Then Zora came over one day to hang with Tsubamé and Raheemah, when they were in year six, and she casually, in the course of some tween chat about pop stars gone quiet, said, “What has happened to JoJo Siwa? It’s like she’s been akumatized,” no explanation needed, they all knew exactly what she meant—as did I!— and what a great bit of off-the-cuff linguistic assemblage that was.

**Park is coming to the UK soon: 1 April - Cafe OTO, London; 3 April - St George’s, Bristol; 4 April - Opera North, Leeds.