#18 'Between the earth and silence'

Night winds, billowing kites, eternal atoms, Egyptian beans, sun tunnels, space trains and a sky stuffed with stars

David, a friend with whom I lost touch a whole lifetime ago, first introduced me to WS Merwin when we were both teaching languages to rich kids from Paris in a nondescript bit of Belgium (one floppy-haired tween vouvoied his parents; the fathers of several were MPs; none of them had any sense).

Merwin’s poetry has gripped me ever since. The expansiveness of it all, his ability to draw a universe in five sentences, and place you, in all your tiny specificity, within it. Perhaps my favourite of his poems is Utterance:

Sitting over words very late I have head a kind of whispered sighing not far like a night wind in pines or like the sea in the dark the echo of everything that has ever been spoken still spinning its one syllable between the earth and silence

As a companion piece to my interview with Katie Paterson—which I’ll publish tomorrow—, here’s a fitting list of expansions I’ve collected for you these past couple weeks.

The enduring mesmerisation that is Samantha Harvey’s Orbital and her descriptions of the Earth from outside of it:

“There’s the first dumbfounding view of earth, a hunk of tourmaline, no a cantaloupe, an eye, lilac orange almond mauve white magenta bruised textured shellac-ed splendour.” p79

“The sights from orbit do this; they make a billowing kite of you, given shape and loftiness by all that you aren’t.” p102

Rikuto Fujimoto, A Bearing Tree — and all the tracks on this 2024 album, Distant Landscapes (thank you Akin; all tracks in the playlist down below)

Ichiko Aoba, whom I interviewed for a piece that published last week, whose new album Luminescent Creatures will soon be out:

Cai Guo-Qiang’s Sky Ladder (you can watch a documentary all about it on Netflix)

These ice stupas in Ladakh: such an ingenious harnessing of one natural phenomenon to remedy the way we’ve screwed up so many other natural phenomena:

This bit in Lucretius’s De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of the Universe), Book II*

Once more, we all from seed celestial spring, To all is that same father, from whom earth, The fostering mother, as she takes the drops Of liquid moisture, pregnant bears her broods- The shining grains, and gladsome shrubs and trees, And bears the human race and of the wild The generations all, the while she yields The foods wherewith all feed their frames and lead The genial life and propagate their kind; Wherefore she owneth that maternal name, By old desert. What was before from earth, The same in earth sinks back, and what was sent From shores of ether, that, returning home, The vaults of sky receive. Nor thus doth death So far annihilate things that she destroys The bodies of matter; but she dissipates Their combinations, and conjoins anew One element with others; and contrives That all things vary forms and change their colours And get sensations and straight give them o'er. And thus may'st know it matters with what others And in what structure the primordial germs Are held together, and what motions they Among themselves do give and get; nor think That aught we see hither and thither afloat Upon the crest of things, and now a birth And straightway now a ruin, inheres at rest Deep in the eternal atoms of the world.

Two Lanes, Reflections:

This piece by Aaron Parrett, about Lucian of Samosata’s Vera Historia, a second-century satirical text that is, quite possibly, the earliest example of sci-fi (it describes a trip to the moon; Lucian was a Greek-Syrian rhetorician born in present-day Turkiyë)

In his Menippus dialogue, Lucian seems sure that knowledge itself is a function of perspective, and that the base fact of being earthbound ensures that we cannot have an unbiased and objective view of any “truth”. From the moon, he sees the world as a small and fragile object, upon whose surface wars and empires appear absurd: “And when I looked to the Peloponnese and caught sight of Cynuria, I noted what a tiny region, no bigger any way than an Egyptian bean, had caused so many Argives and Spartans to fall in a single day.” 1,800 years before humans even ventured into space, Lucian articulated a sentiment that almost every astronaut fortunate enough actually to have traveled into space and looked back at the earth has also voiced: a profound and nearly religious sense of the fragility of our planet, our “pale blue dot,” as Carl Sagan called it.

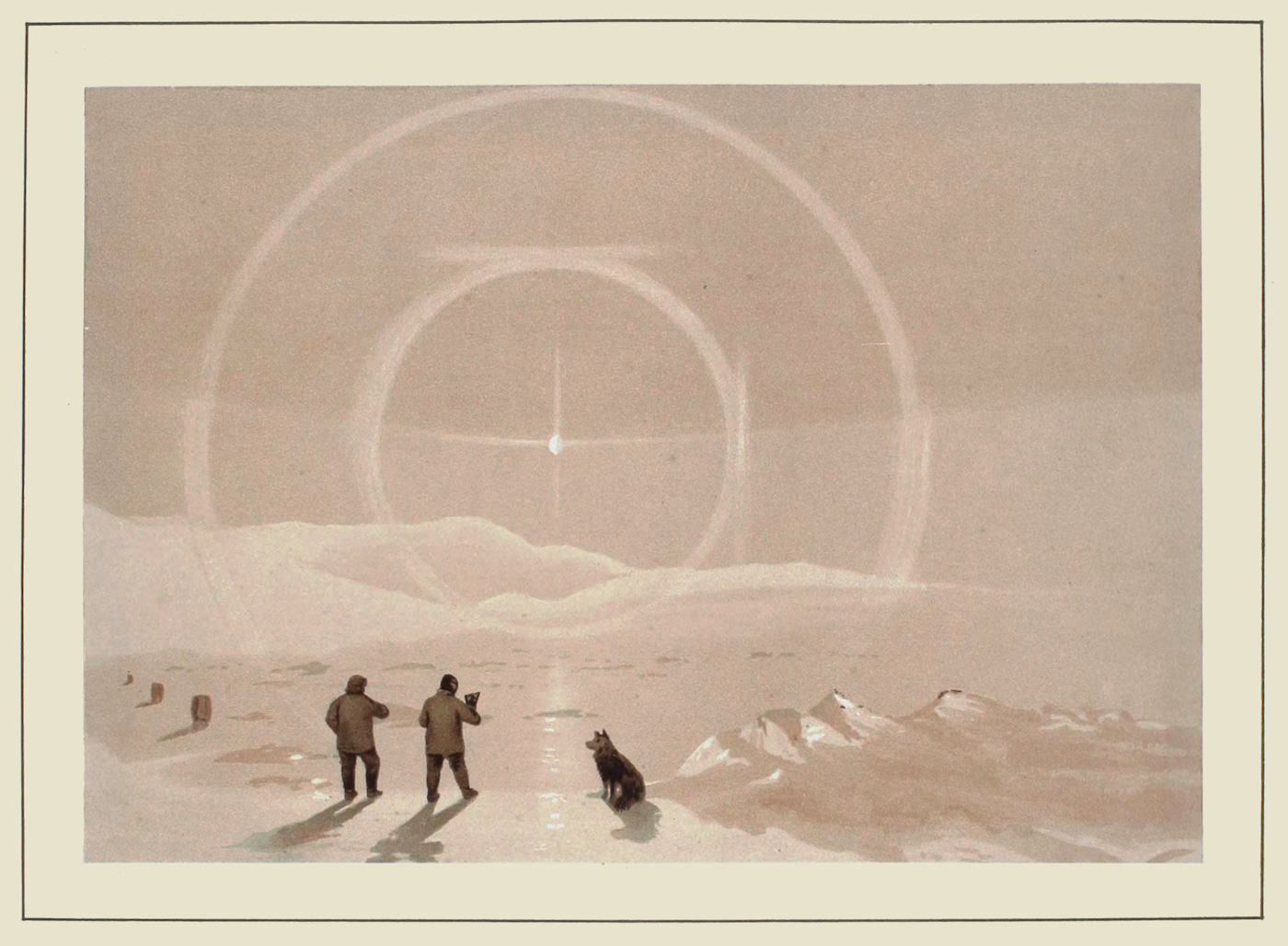

Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels, 1973-1976 (photograph: Retis), which I wrote about a while ago, here …

… and this performance the Indigenous Canadian musical duo Eagles with Eyes Closed (formed by artists Tobias Linklater (Alutiiq/Omaskêko Cree) and his father, Duane Linklater (Omaskêko Cree)) did for DIA in 2021, in response to Holt’s 1978 film on the making of the Sun Tunnels, which sit on Shoshone and Goshute ancestral land in Utah:

Jean Follain, Music of spheres:

He was walking a frozen road in his pocket iron keys were jingling and with his pointed shoe absent-mindedly he kicked the cylinder of an old can which for a few seconds rolled its cold emptiness wobbled for a while and stopped under a sky stuffed with stars.

Space trains! From The Book of Knowledge, The Children's Encyclopaedia, Volume I. (1910, The Grolier Society)

Shabaka Hutchings, whose magical flute journey continues apace. I’m stuck on this track rn, Living, the album version features Eska on vocals and is just magnificent (in the playlist below). Here’s a live version:

Notes

*I’d only ever experienced this book in French until this week when I finally got a copy in English. This excerpt is from the 1916 translation by William Ellery Leonard and EP Dutton, whereas mine is from 1951, by Ronald Latham. I have no idea who these men are, but 1) I like full names. And 2) I also love the sense of millennia you get when you compare translations.

In the 1916 translation, you read “Till nature, author and ender of the world / Hath led all things to extreme bound of growth.” Which, in 1951, Latham renders as: “At length, everything is brought to its utmost limit of growth by nature, the creatress and perfectress.” My French version meanwhile, from 1984, is unexpectedly matter-of-fact, by comparison—it reads like a scientific treatise, not a poem and helps me understand better. Here the line is prosaic “C’est alors que s’arrête le progrès de la vie pour tous les êtres ; c’est alors que la nature intervient avec ses forces pour réfréner la croissance.”

Latham’s translation, with its “the creatress and perfectress”, immediately made me think of Hebrews 12:2, and the endless iterations through millennia of translations (in various Englishes: “Let us fix our eyes on Jesus, the author and perfecter of our faith” > the source and perfecter > the author and finisher > the originator and perfecter > the founder and perfecter > the pioneer and perfecter > the founder and completer > the leader and perfecter > The Author and The Perfecter > the beginner and perfecter > the first incentive for our belief and the One who brings our faith to maturity … > in ancient Greek: ἀρχηγὸν καὶ τελειωτὴν AKA archēgon kai teleiōtēn >ונביטה אל ישוע ראש האמונה ומשלימה אשר בעד השמחה השמורה לו סבל את הצלב ויבז החרפה וישב לימין כסא האלהים׃ in Hebrew >ܢܚܘܪ ܒܝܫܘܥ ܕܗܘ ܗܘܐ ܪܝܫܐ ܘܓܡܘܪܐ ܠܗܝܡܢܘܬܢ ܕܚܠܦ ܚܕܘܬܐ ܕܐܝܬ ܗܘܐ ܠܗ ܤܝܒܪ ܨܠܝܒܐ ܘܥܠ ܒܗܬܬܐ ܐܡܤܪ ܘܥܠ ܝܡܝܢܐ ܕܟܘܪܤܝܗ ܕܐܠܗܐ ܝܬܒ ܀ in Aramaic < fairly certain both those need to be read from right to left. And oh how I wish I could read all this in the originals just like Anne Carson.)