#2 'Our time can be cut short'

On death and being storm and the need to make something beautiful

Of the magnificent pairing of photographers Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron, that the National Portrait Gallery recently devised, what has really stayed with me are the two firsts, with which the show (titled Portraits to Dream In) began.

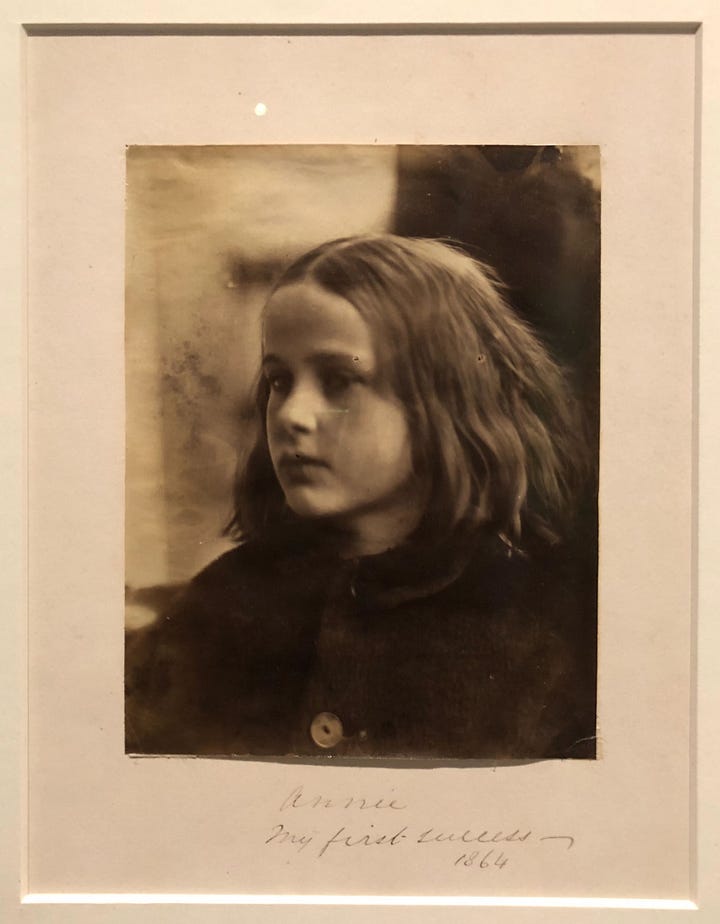

Woodman’s Self-portrait at Thirteen, 1972, and Cameron’s self-titled “first success”, Annie, January 1864, which she took when she was 49.

Woodman was the precocious talent who didn’t live past 22 yet made a body of work so indelible, it towers as tall as a giant redwood. Cameron, meanwhile, didn’t pick up a camera until she was 48. But she too, with all the urgency in the world, made works we cannot ignore. I’ve been thinking about why this is. What makes something so magnetic? What is a beautiful thing? And what makes us make them urgently?

Patti Smith once said that all she'd ever wanted, since she was a child, was to do something wonderful. In his lifetime, Freddie Mercury built up a collection of what he called splendid things. When Gainsbourg, meanwhile, showed a TV crew around his home one spring day in 1979, he said: “Well, this is my house. I don’t know what it is: a sitting room; a music room; a mess; a museum.” But any perceived mess belied a deeper intent: “Everything is calculated according to particular rhythms.”

Not long before she died, on November 5, 2022, Mimi Parker told an interviewer that making music over the two years since her cancer diagnosis had been “a respite and a source of comfort”. Parker was a drummer and a singer, and the beating heart of Low, the band she formed with her husband Alan Sparkhawk in 1993.

“Our time can be cut short,” she said. “I’m thankful for the experiences I’ve had, the opportunities to make beautiful music, to collaborate with Alan, to understand his chaos and his tendencies to mesh them with my calmness and my search for harmony and beautiful things.” Parker was a beautiful person. She lived to 55.

My baseline criteria for how beautiful a thing — an artwork, an exhibition, a piece of music, someone’s writing — really is is whether it makes me want to make something. Whether it breathes light into my eyes and sets my mind afloat.

I’ve also been thinking about how describing a really good artwork as a pièce de résistance sometimes makes sense literally. Linguisticians do not agree on how that phrase came to denote le plat principal, the main affair, a masterwork. But I like the idea of a thing of true beauty being something that can resist.

I think this is exactly what sustained the Chilean artist, Cecilia Vicuña, in her decision, in 1973, to make an object a day in support of the revolutionary process in her country. She was in exile. President Salvador Allende and democracy were dead. The Chilean people were being forcibly shut down. Vicuña duly wrapped ribbon and thread around a feather atop of a piece of bark. She sewed a star on to a piece of felt and the felt on to a piece of card. “The objects try to kill three birds with one stone,” she writes in A Diary of Objects for the Chilean Resistance. “Politically: stand for socialism. Magically: help the liberation struggle. Aesthetically: be as beautiful as they can to reconfort the soul. give strength.”

Vicuña’s Objects for the Chilean resistance are of a piece with the diminutive sculptures that she had started making in the 1960s and still does, with the stuff and detritus she finds when out and about. She calls them precarios, which you might translate as “precarities” or “precariouses”. In the recent exhibition at the Barbican, Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Vicuña had a large-scale installation, but it is the roomful of her precarios that stopped me in my tracks for their quiet grace.

Similarly, what I loved most in the current survey show of Phyllida Barlow’s work, Unscripted (which I reviewed for the Guardian here), were the tiny new sculptures, the maquettes for bigger installations, the drawings that all attest to that thing that Charlotte Higgins wrote back in 2017, which immediately took root in my mind like a tree: “She has, she said, always made her art ‘as if a storm were coming’.”

Dominique White’s works, by contrast, are almost always outsized but each is dwarfed by the maelstrom it contains. Ahead of her current show, Deadweight, at the Whitechapel (on until September 15), she told me that she likes to push her materials, (kaolin clay, metal, sisal rope) in unconventional, uncomfortable directions. Barlow too would drop and bash structures to see how far she could take them.

“I've had works completely destroy themselves in the studio,” White said. “I've smashed a couple of pieces of iron from sheer force, from being a little bit too daring. It's always like a pushing of everything to its limits, but also leaving it all very vulnerable.” She calls her work anti-sculpture, because she’s always turning trad methods on their heads. She builds with crumbling clay and unweaves woven things; much of the metal she used in Deadweight, she first submerged in the sea for a month — quite literally weathering storms.

Like the precarios, White’s works emerge as if out of troubled air or geological disturbance. They’re resonant — resolute — with fragility and strength both.

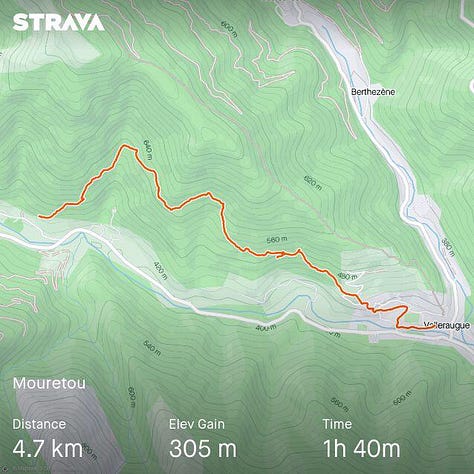

I’m in the Cévennes right now, for a month. It’s baking hot, but we also have these épisodes cévenols that roll in from the Atlantic and get stuck against the mountains, lasting for days, tipping waterfalls down every rockface and causing shy rivers to burst their banks. Soon, I’ll tell you about Viviane Dalles, a photographer who lives up the road and is documenting the devastation such storms and their floods cause. Also, a new film by Eliane de Latour, titled Animus Femina and scored by the magical Piers Faccini, with whose recent song I leave you:

Notes

There are existential storms and deadly storms. And then there’s Twister, the original 1996 stormchaserfest, a legitimately excellent thing to watch and I do so, regularly. It has Weather, wind chime sculptures, maps and flying cows, Philip Seymour Hoffman in a faded hoodie, Lois Smith as the other aunty you wish you’d had, lines you’d also still be quoting if you’d first watched the movie with your sister when you were both teens, and a Repo Man reference. (Also, my friend Dave, newly of this parish, moonlights as an actual storm chaser and written about it here, here and here. )

World of Echo

Benson Boone, Beautiful Things (because it’s my kid’s favourite song atm)

Ballaké Sissoko ft Piers Faccini, Kadidja

Françoise Hardy, Le premier bonheur du jour

Pull up a memory

I told you last week that that is how my friend Dan sometimes greeted us in the studio, when we shared a studio at the Slade. He replied with this:

🥰 So, like, yes please, send me stuff?

The walk and talk

Me in the Cevennes; and my godson Arthur, who walks shapes around London.

Every time a Francessca Woodman image appears I, like you, find light breathed into my eyes and my mind set afloat— loved this mediation on beauty!Her work happened to be the first to bring tears and inspired me to pick up a camera time after time.

Your newsletter is one of the few that I’ll be devouring as soon as it arrives