End-of-week treats #13: 'Heard it’s 90% endurance , keep going m8'

The Bear, Lotto Ash/Imrhan, Little Simz, Pixy Liao, William Kentridge, Rilke, Matthew, Isaac Rangaswami, Arvo Pärt, Loyle Carner, Cezanne, Katie Paterson, Tilda Swinton on Derek Jarman, Blue Lake

In episode eight of the fourth season of The Bear*, Tina (Liza Colón-Zayas), now the restaurant’s sous-chef, is beyond frustrated. She’s trying get her timings down by 30 seconds on a particular pasta dish, to make it in less than three minutes. But the timer just won’t budge. It consistently shows her over budget.

“That’s the pressure,” Luca (Will Poulter) tells her.

“How do you get rid of it?” she asks.

“I think you get to a point where you don’t want to,” he replies. “Like, at first the pressure sucks, right? It’s the pressure that makes you feel shitty at what you do. And actually that’s just the pressure getting in the way. You learn to live with it. And the next thing you know, you thrive on it. And before you know it, you can’t fucking wait to get rocked, like, you want that pressure, you need that pressure, to be able to perform. So then, the challenge actually becomes, can you live without that pressure?”

“Can you?”

I can relate. I’m trying to write and make things that I don’t have a deadline for. That absolutely no one is asking for. Sometimes, though, I get so locked into that journalism gear of writing to deadlines** and being on it — seeking out the urgent — that my mind buzzes most when it’s about to explode but then when the pressure subsides, I deflate completely. I lose myself. The quiet that follows overwhelm is unhelpfully discombobulating. So I’m trying to get better at shifting gears, at finding balance. I want my own work to take up the same quality — if not quantity — of space and energy that work-work takes. I want my own work to breathe, too.

I told you I did a gig in Paris a few weeks ago — you can listen here.

It was the first time I’d properly performed live since I was pregnant with my kid and I felt like I was flying. That’s a feeling I want to hold on to but it’s not easy when must-do things are clinging to my ankles and my mind is mush. So I’ve been walking a lot and thinking a lot about what it takes to keep going. On his new album, Hopefully!, Loyle Carner sings “I can't figure out how to take it slow, but / You feel like home”. He’s probably talking about a relationship. But those words could also be some kind of enjoinder to balance out both “striving” with “being” — and “trying”, with “coming home” — and “home” could be Woolf’s “a room of one’s own”, Voltaire’s “garden”: this inner space that anyone who’s trying to make something feels the need to protect, in whatever way they can, so that the thing, The Thing, actually gets made. Anyway, here, some things that I hope bring you something too. <3

The legend that is Little Simz just posted this this week “Heard it’s 90% endurance , keep going m8 🤲🏿✨” — the hug I needed.

I just can’t get enough of her album, Lotus — and Lion in particular.

Photographer Pixy Liao’s solo show, which opens at the Art Institute of Chicago on July 26, comprises 45 works mostly from an ongoing series she started in 2007, in collaboration with her partner, Takahiro Morooka. “Moro and I have been collaborating – and living together – for 13 years now,” she told me in 2019. “Each image reflects my thinking about our relationship at that particular moment: together, they’re like a notebook, a record of our history.” I love this work so, so much for its wit, its daring, its playfulness.

Carner’s new album, Hopefully!, is properly beautiful. The lyrics, the drawings by his little boy that he’s included, the rhythms, the whole vibe …

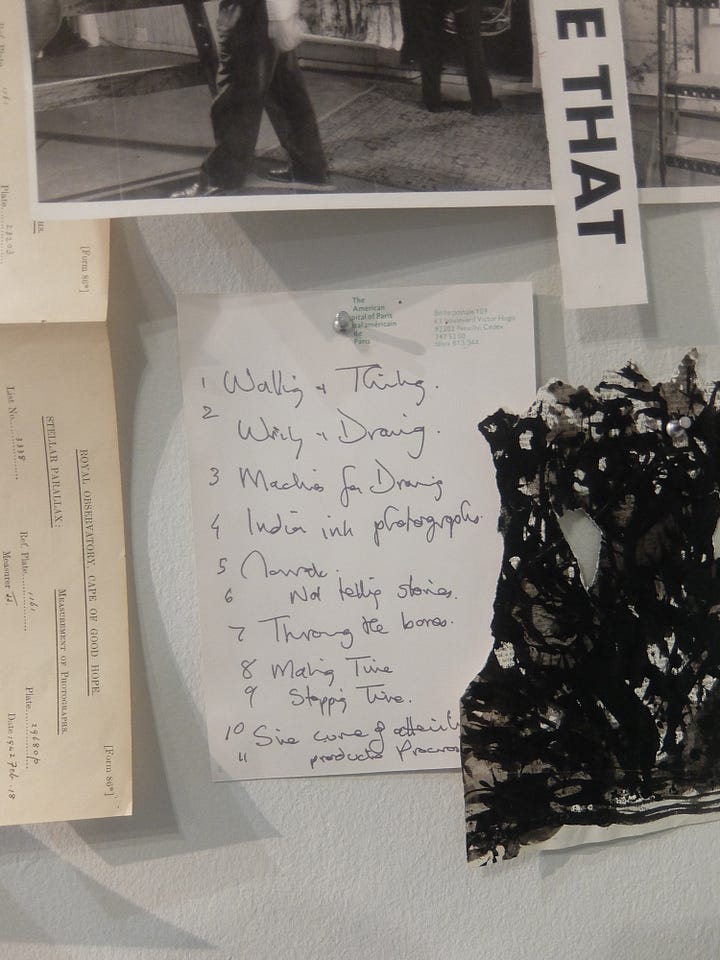

I interviewed William Kentridge for the Guardian recently, along with a few of his longterm collaborators, ahead of his new show, The Pull of Gravity, at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, which I also reviewed for the Art Newspaper.

“There’s a branch of Hasidism,” he told me, “that believes the words of the prayer are for God and the gaps between the words – the white spaces – are for you. That’s me. In the moment of listening, I absolutely get lost.” Pianist Kyle Shepherd described Kentridge as a jazz man on a level with South Africa's greatest – the pianist Abdullah Ibrahim, the flautist and saxophonist Zim Ngqawana. And Nhlanhla Mahlangu described working with Kentridge as "moving through the cracks" — and spoke of Kentridge as "a comrade".

The first time Kentridge asked Belgian set designer Sabine Theunissen to propose a design for a production he was working on, she made a maquette so small it fit into a matchbox. “He didn’t even look inside,” Theunissen told me. “I think it’s because I immediately started making something. And we still work in the same way.”

Kentridge has never minded working out loud, as it were: “There are some artists for whom it is very important not to talk about what they’re doing while they’re doing it,” he said. “But I’m someone who works easily and well with people seeing work in different stages. While they’re watching the film, I’m watching them – to see things that are connecting and those that are not.”

This has got me thinking. One of my current writing projects is a bitty thing, the process of which I’m considering opening up and doing a bit like he does, out in the open, on here. As an experimental framework, a different kind of deadline or pressure. Would you be up for reading instalments as I go?

Last week, Avery (<3) sent me this excellent collection of portraits from behind, of people at work in London, by food writer Isaac Rangaswami (read his work on Vittles and the Guardian).

Which, for some reason, made me think of this 1998 New Yorker piece I read a whole lifetime ago, about a fashion saleswoman called Victoria going for her very first interview at Prada in a bright orange pant suit (i improved the scene in my spotty memory and remembered it as a prison-style jumpsuit) bc expensive black chic was not, remotely, her world, and yet, somehow going on to totally smoke them all. It’s the blinding, ballsy graft of it all that’s always stuck with me:

All good salespeople are great record-keepers, but Victoria was an exceptional one. She used this skill to cope with her new surroundings. She bought a loose-leaf binder and divided it into sections—one for time zones (“If you’re in New York, don’t call people in L.A. at 10 a.m.”), and another for maps (“I’ve got customers from Zimbabwe. You’d better know where Zimbabwe is if you’re gonna keep ’em”). She made calendars to keep track of her work hours, her appointments, her alterations, and her sales. She designed a client questionnaire that she could pass on to the buyer: it posed questions such as “Tell me what items you would like to see stocked at our store,” and “What is it about Prada that you like best?” She put all this information on a small handheld computer, which she set to beep her on important dates like client birthdays. “In the beginning,” Victoria told herself, “you build.”

I recently spent months speaking, texting, videoing and writing with Katie Paterson for the New York Times, ahead of Amulet, her new commission for the Folkestone Triennial. Of the many things she told me, this sticks out right now. For her MFA degree show at the Slade School of Fine Art in 2007, she wrote a working cell phone number 07757001122 in neon-tube lighting on the wall. Viewers could call it from anywhere in the world and listen to the sound of the ice river melting into the Jökulsárlón lagoon in Iceland. Of course, this was a student show, so she remembers some dubious banter, peers saying, “Oh, is it just you in the toilet, you know, splashing around, or you in the bath with a microphone?” She was horrified. “I was like, Nooooo, are you serious? Do you know what it's taken to get a signal out there and get equipment that is sealed and all that stuff? I kind of set myself up from the beginning, I think, to just be like this, and I can't lighten things up anymore. It's strict and it's real.”

For another piece, for the Guardian’s Saturday magazine, I went back to Aix to walk in Cezanne’s footsteps, pegged to the big Cezanne au Jas de Bouffan exhibition that’s just opened. After spending an hour with both curators – the current director of the Musée Granet, Bruno Ely and his predecessor and current director of the Société Paul Cezanne, Denis Coutagne, the one suggested to the other that they lunch promptly. "We've to be back at 2pm for another hanging," said Ely. "Ah, the Lausanne," said Coutagne, the 40 years of Cezanne scholarship they share resulting in a shorthand that reduces each work to where it lives in the world. We descended to the back office entrance on rue Roux Alphéran — above which there's a sign for the erstwhile Ecole spéciale gratuite de dessin Cezanne attended as a teenager. In the lobby, Coutagne pointed at a poster for a former Cezanne exhibition — depicting a landscape — and said, "That's a rock we've identified. We know exactly which one it is." I watched them walk up the road, two pairs of shoulders hunched over their white-haired heads like quotation marks around the Cezanne lore that simply flows from them, unimpeded. Such singular purpose. Such devotion.

I’m still thinking about Arvo Pärt in 2020 referencing John Updike on medieval sculptors “who carved church pews in places where it was impossible to see them”. Because hard work so often is not usefully visible. Or acknowledged. Being seen is not necessarily what gives the sense of purpose needed to keep going.

A case in point: Koji Yakusho in Wenders’ Perfect Days:

Which, as all things seem to at the moment, brings me back to Rilke, again, with this bit from Prayerful Hands, in The Book of Hours:

All else being vanity, only prayer is real. Our hands are consecrated to excel in sacred work – to love, repair or make, all forms of supplication. Whether we're skilled at painting a Virgin or ploughing a field, we express our faith by mastering a tool.

I love the idea of sacred work, of work as prayer. Or of prayer as work. And the question about what really qualifies as “rewarding” (“But when you pray, go into your room, close the door and pray to your Father, who is unseen. Then your Father, who sees what is done in secret, will reward you.” Matthew 6:6)

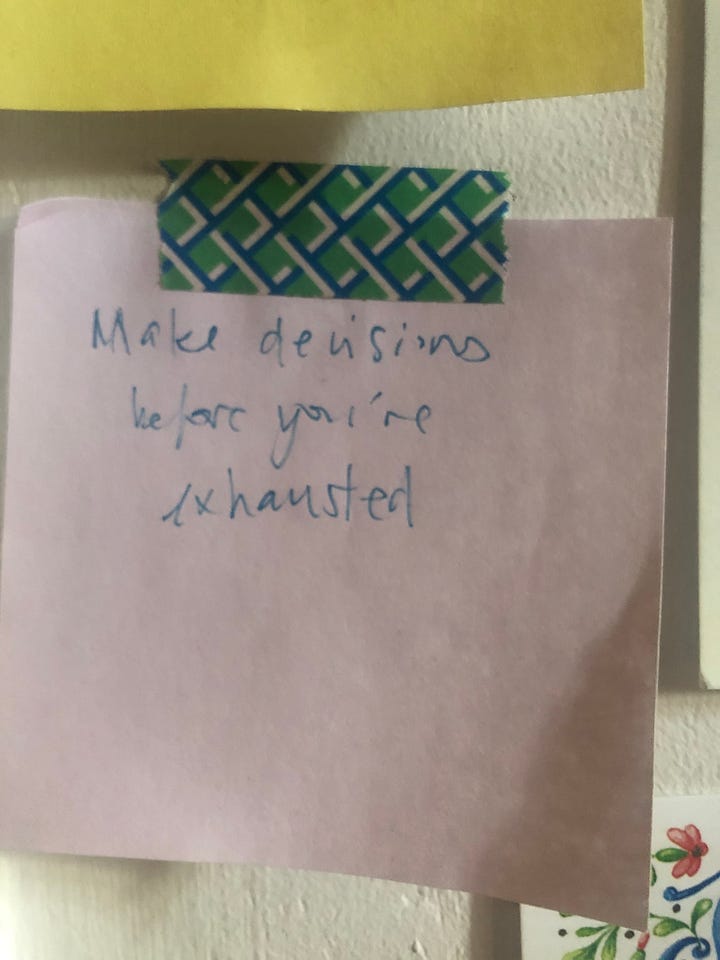

Two things I’ve had on my wall for months which help when I look at them, can’t remember exactly where I got them.

Today I’m writing about Derek Jarman. For a 2024 monograph Tilda Swinton wrote an open letter to Jarman, gone these past 31 years. Of her readers, she says, “I might as well let them in on the trick — that the conversation is not done yet … that the company you keep with us, when we care to think of it, is just as strong and empowering as it ever was. That the example you set is as simple as a logo to sell a sports shoe; less chat, more action, less fiscal reports, more films, less paralysis, more process. Less deference. More dignity. Less money. More work. Less rules. More examples. Less dependence. More love.” I think that’s wonderful.

Been singing to the beautiful first track, Cut Paper, from Blue Lake’s new album – everywhere (along with Big Thief’s Cattails and Eddie Vedder’s Save It For Later).

To end with, this freestyle from Lotto Ash/Imrhan and the voicemail from his mother he includes at the end. The way she says, “Keep going” …

Laters, babes. Keep going. Send me stuff. Walk with me (I’ve decided to do at least 10km a day this summer — you in? Find me on Strava if you are? ). And buy yourself some flowers, as my mama always says. I send you LOVE.

Notes

*There’s just not enough time to tell you how much I love this show. The writing, the silences, the soundtrack (quite a few things on my playlist below), everyone sitting under the table, Fak leaning into the flowers, the swearing, the dialogue, the acting, Ayo Edibiri — her micro facial expressions, her outfits, the episodes she’s written and directed, Syd’s relationship with her father, and her impossibly great acting when he falls ill. The fact that Hiro Murai is involved (the man’s worked on Atlanta, the 2024 Mr. & Mrs. Smith, Childish Gambino’s This is America, Frank Ocean’s 2013 Grammy performance videos, Barry!). The realism of the arguments. I’ve always loved Sorkin for his ability to write perfectly worded repartee and argument (Toby in the Wing; Jeff Daniels’s speech in The Newsroom pilot) — or Tony Gilroy’s perfect speeches in Michael Clayton and Andor. But in a real argument, who ever actually talks like that? The Bear creator and writer Christopher Storer does a stunning job at writing the struggle it is to say actually say what you’re feeling to a person looking right at you with all the feelings on their face. So too, the realism of the tenderness — Richie and Tiff just pulling faces and sticking out their tongues at each other in the Fishes episode; the way Richie is with his kid; Syd and her father again, my word. The care. And what it means to cook for someone.

**Other recent pieces I’ve done include bits about visitors to Tate Modern, a Wim Wenders exhibition and new work Jane and Louise Wilson have made using Roman timbers recently recovered in a lost river several stories below ground in the City of London. And, soon to be published, a feature pegged to the 100th anniversary of the Surrealist game, Exquisite Corpse, and a great big working-in-the-kitchen piece for the Filter on the best non-toxic frying pans (if I’ve never cooked for you in real life, you probably won’t know that I do it a lot, and quite often write about it too, as a slightly crazy-making side-hustle).

so many treats! do share your work in progress and yeah m8, keep going 🩶