Katie Paterson: 'I have to put aside the feelings of dread and focus on how wonderful it would be to do this thing'

The Scottish artist has made a career of condensing immensities into small things—or sentences or gestures—and set countless imaginations aflame in the process

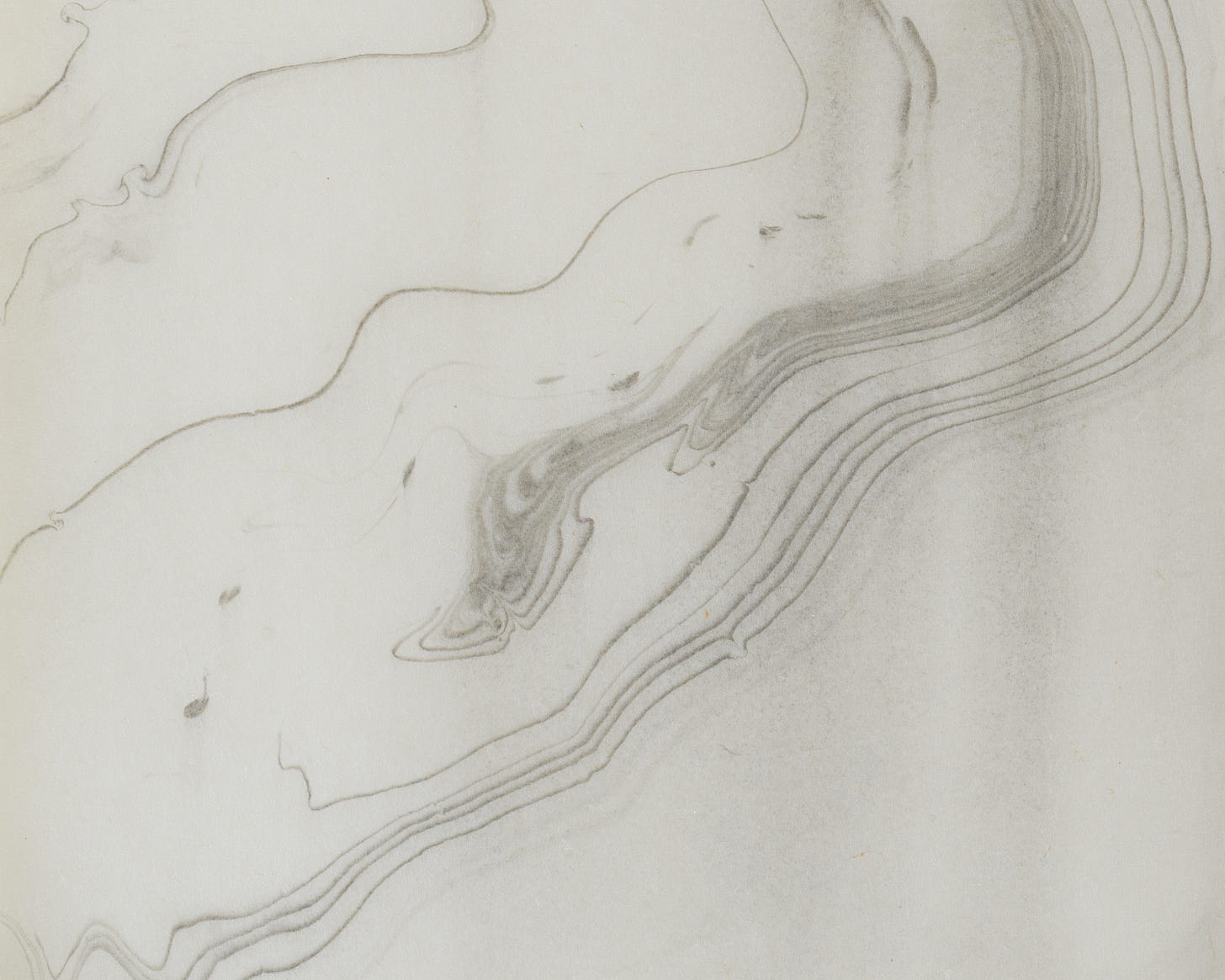

Several years ago, Katie Paterson was given a decommissioned Antarctic ice core from an ice-core library in Denver. After finally figuring out how to get it shipped to the UK, via New York, she stored it in a dedicated freezer in her garage with a back-up system, in case of power outages. She knew what she wanted to do with it. She’d learned about suminagashi, an evanescent Japanese marbling technique, wherein you dip a brush soaked with ink and another with a solution that separates the ink, into a tray of water. The ink draws these concentric circles on the surface that the slightest movement, or breath, will alter. And that delicate interplay is what you capture when laying a sheet of paper on the tray.

Paterson planned to melt the core ice to use as the water, but she couldn’t quite work up the nerve to get started. “I was so scared, so aware this is a technique that can take years, it’s not just something you dash off.” But then something went wrong with a piece she was hoping to put in a show, and she thought, “Right, it’s time.”

It was her son, Emory, who first unwrapped the ice core. Paterson noted the way it recorded history, the changing seasons, volcanic eruptions, all visible in its layers. “Listening to it melt was beautiful,” she tells me, “because the bubbles that are dissolving are literally 1,000-year-old air that you’re breathing in.”

“Did you record the sound?” I ask.

“No, we just listened. And we licked the ice. Well, Emory licked it. The document is now in his body. And I licked it as well.”

We’re talking over Zoom. Paterson is not long back in Scotland after opening There is Another Sky, at James Cohan’s 52 Walker St space in NYC. Alongside her Suminagashi series, she has shown several works including The Moment, a hand-blown hourglass filled with cosmic dust that’s older the sun; Silva (see below), an ikebana-style branch, kiln-dried and lacquered with the ashes of 10,000 trees, representing forests from every corner of the Earth (from ancient woodlands to tropical rainforests to arctic taigas). To Burn, Forest, Fire, meanwhile, is a set of two incense sticks, made in concert with geologists, ecologists, botanists and Japanese incense makers, that perfume the air they’re burned in with the scent of the Earth’s first forest—and that of what is likely to be its last*.

One-thousand-year-old air and a popsicle. Interstellar matter and a vintage timepiece. Three hundred and eighty-five million years of sylvan life on Earth and a slim stick of scented senkou, like those I burn most days in my living room (see too, the “stick of time” in Shogun, incense as a way to measure how long an audience the lord might grant any one person).

Running through Paterson’s oeuvre is this twinning of incongruities: some incomprehensibly outsized thing (the expanding universe, a planetary lifespan) juxtaposed with a very 1980s small-town thing (a glitter ball, a confetti cannon, a dimmer switch, a talking clock). Together, they chime out loud a sense of wonder—and endless questions.

In the book of ideas, A Place That Exists Only in Moonlight, that Paterson published in 2019, “Records of glacial ice played until melted” is slotted in between “The scent of extinct flowers recreated” and “A molten meteorite cast back into its first form”.

Scroll through her online portfolio and you will also find among her earliest works, Langjökull, Snæfellsjökull, Solheimajökull, from 2007, with the following description: “Sound recordings from three glaciers in Iceland were pressed into three records, then cast and frozen using the meltwater from each corresponding glacier. The discs of ice were then played simultaneously on three turntables until they melted completely.”

In other words, she did it. She produced the ice record with the sound of the glacier melting. “My kind of, I suppose, dream life would just be thinking up things,” she says. “But then something still compels me to make some things.”

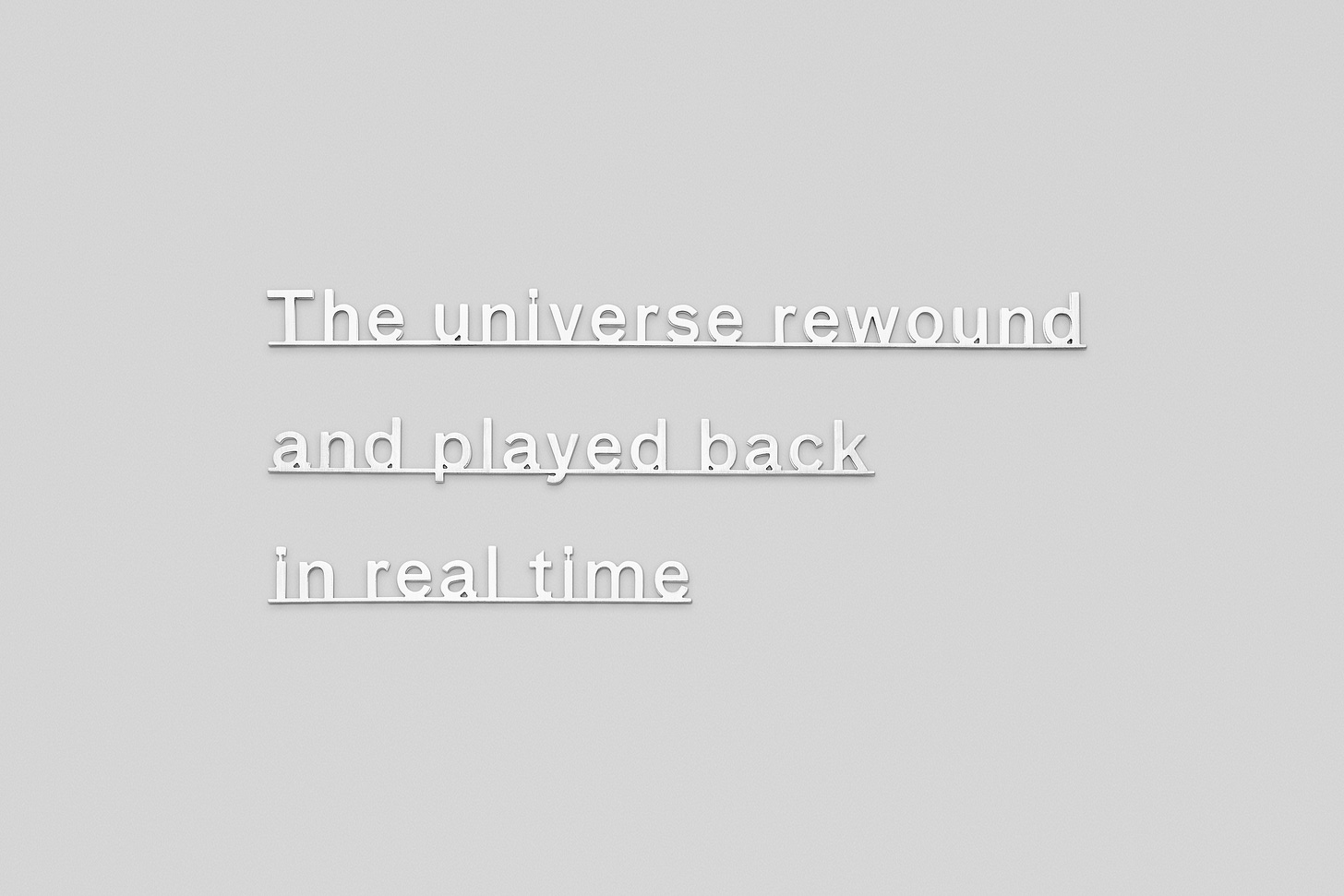

She has been writing and collating her Ideas sentences from the beginning, it’s what she presented for her final Critical Studies component of her MFA at the Slade School of Fine Art in London. She exhibits them too (see above), the words cast in silver to be hung on a wall. But each one, like a marble, also contains within itself an iridescent swirl of possibility or at least hope, however unrealistic, that it might actually come to be.

Paterson is best known for realising her biggest idea: Future Library. Born in a sentence found towards the beginning of the book—“A forest of unread books growing for a century”—this project came to life in 2014, when she planted 1,000 Norwegian spruce trees in the Nordmaka wilderness area north of Oslo and commissioned the first of one hundred manuscripts that different international authors will write every year until 2114. In 2022, she opened the Silent Room, a timber-lined space on the top floor of Oslo’s Deichman Bjørvika public library, in which to store them. Each is sealed in a glowing glass drawer etched with the author’s name and the year of their submission. When the 100 years are up, the trees will be harvested and processed to make the paper on which to print an anthology of those 100 books. People will finally get to read them.

The first author to say yes was Margaret Atwood and you immediately get why. “I think it goes right back to that phase of our childhood,” she beamed, shortly after the announcement was made, “when we used to bury little things in the backyard, hoping that someone would dig them up, long in the future, and say, 'How interesting, this rusty old piece of tin, this little sack of marbles is. I wonder who put it there?’” Books, she said, are always like messages in a bottle; all the more so, these sealed manuscripts, to those future readers, who might, she cautioned, need “a paleo-anthropologist” to translate some of what at least she has written for them: because language will be different by the 2110s.

“Future Library plants a flag for delayed gratification in the quicksands of the social media age,” one leader column—not commonly something an artwork elicits—noted in 2022. “The 100-year deal signed with the city of Oslo guarantees protection of both the plantation and the books. The contract is no mere bureaucratic aside, but an essential part of a project that is not yet a tenth of its way to completion, and will rely for much of its life on custodians who are yet to be born.”

In many ways this—time beyond any single lifetime; space beyond the confines of our dying bodies—is always what Paterson is working with. Waterdrop (see above) saw her encode a map of the universe into DNA data, suspended in a drop of water, then release that drop into the Goðafoss waterfall in Northern Iceland. From there it was carried out to sea, a real-life Interstellar moment if ever there was one, and an instance of art demanding faith: that you trust that that is really what she’s doing in that grainy greyscale photograph.

For a long time, I wasn’t sure Paterson’s written Ideas could be topped. I wondered if making them happen was even necessary. Faced with a sentence like “Pearl inlaid where snow has melted”, surely a poet will ask, “But aren’t those words enough?”

It was seeing Paterson’s Fossil Necklace delicately hanging mid-room in her 2019 show at Turner Contemporary in Margate that changed my mind. She describes the piece, beautifully, as “a string of worlds”, each bead carved from a fossil that represents a geological era on Earth. It’s not that the object itself is the most beautiful thing in the world or anything: it’s how it pinpoints, with such lightness of touch, the actual beauty of the world, how it makes you sit with it.

“When we started cutting open the fossils,” she says, “each revealed these little worlds with hidden colours and textures and forms. By the time we really carved them into those tiny beads they looked like tiny—or distant—planets.” She experienced an uncanny micro-macro moment, she says, when performing her piece, Earth-Moon-Earth (Moonlight Sonata Reflected from the Surface of the Moon), at the planetarium in Milan in 2014. Outside there were all these posters, which, when she saw them, she took to be images of her fossil beads. “That's strange,” she thought, “We hadn't talked about that work.” And then, of course, she realised, “Oh my God, these aren't the fossil beads, these are actual images of Mars …”

Making the piece marked a shift for her too: “I think that's when I realised how much I love materials. I loved the vulnerability, the fragility, the idea that stones that were bones would hold the residue of what that living thing had been, millions of years ago."

You might say Paterson uses numbers (a hundred, a thousand, those ten thousand trees) in a biblical way (“ten thousand times ten thousand their number, thousand after thousand after thousand in full song”, as per Revelations 5), to denote “everything” or “all” or “as much as can be known”. At the same time, she is nothing if not completist, always aiming for exactitude, counting things inexhaustibly. She gets completely obsessed, she says, with what she calls “the hunt”.

With Fossil Necklace, it was finding the 170 stones for each geological era. For Mirage, a public artwork commissioned by Apple for the Visitor’s Center at Apple Park in Cupertino, California and installed in an olive grove on the grounds of the campus in 2023, it was figuring out how to get sand from each of the world’s deserts (they reached 70). The research then turned technical. In collaboration with architectural studio Zeller & Moye, she had to figure out quite how to make glass out of wild sands, then fabricate the 400 2-metre-tall glass columns the piece is comprised of***.

For Evergreen, Paterson enlisted her mother’s help to compile a list of all the extinct flowers in the world, because, to her amazement, one didn’t yet exist. The final roster counts 351 species.

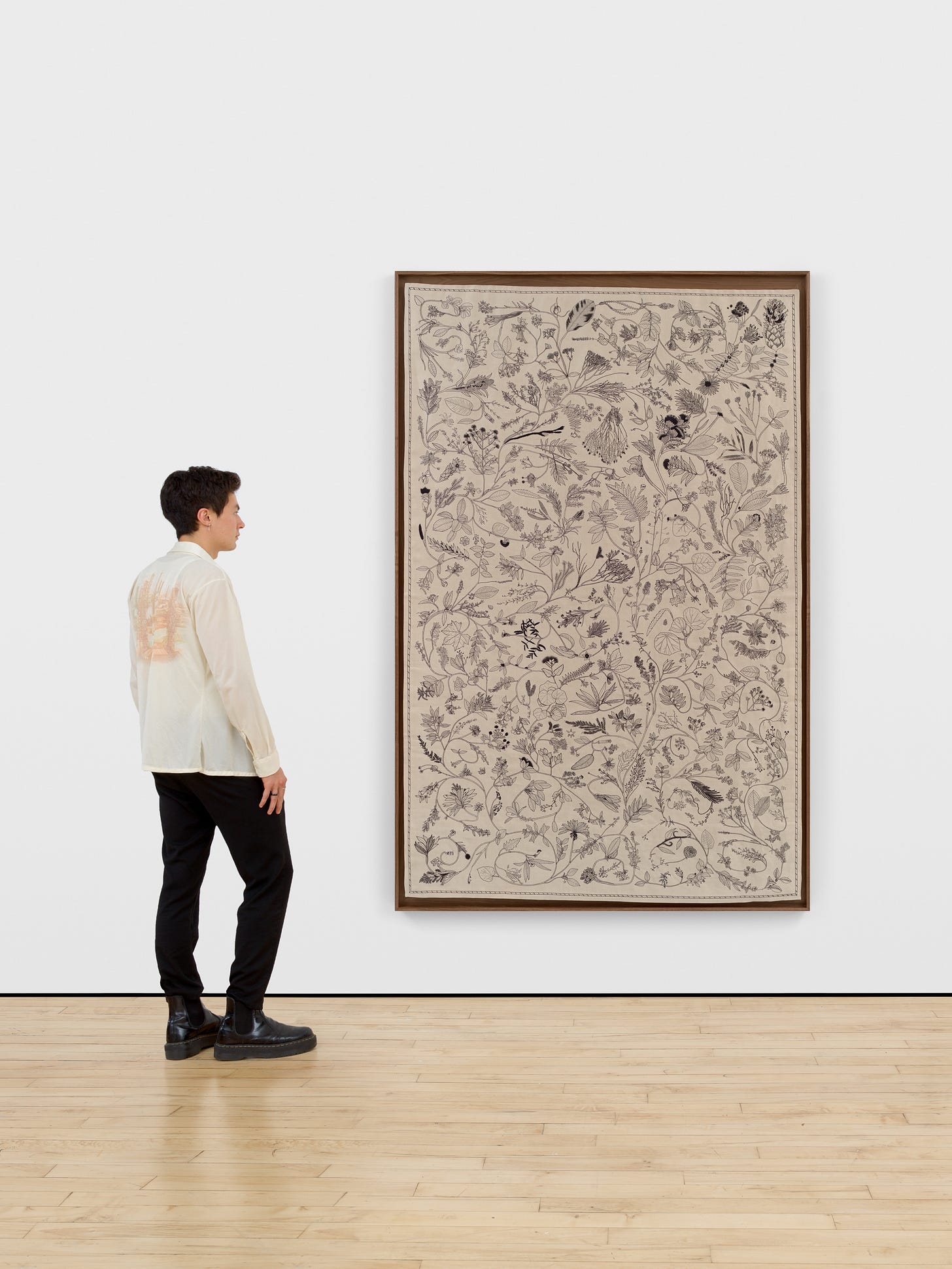

She then worked with a botanical illustrator and the Royal School of Needlework to create an embroidered botanical miscellany depicting those flowers, in the Arts and Crafts style of May Morris’s fabled Owl design. “There were 10 people working for about five months,” she says, “each on a very small patch, responding to the drawings in really tiny stitches. By the end, they figured there were maybe a million stitches.”

“I’ve done it again,” she thought, “Somehow, something seemingly simple, an embroidery to put on a wall, has become extraordinarily complex.”

To properly sit with one of these objects is to hold something much bigger than its physical form in your thoughts. Each one operates as a container and a tool; a lens and a magnet. It trains the initial idea, like a glass does the light of the sun, to start a fire: it both absorbs and explodes our sense of where/what/when we are. Paterson describes making these pieces as “attempting to gather this epically obsessive nature of mine that I can't seem to stop. Wanting to bring these immensities into something that's small and intimate.”

And she’s always trying to see just how small a thing can be. “I've got this crazy spreadsheet going with 1,000 or more Ideas. I’m now thinking about projecting them in light, very, very small—to make them even more ephemeral, so they sort of appear and disappear. It's getting even more reduced.” I tell Paterson about British artist Richard Deacon recently describing marbling to me as “printing on water” and she glows. “I love that,” she says. “That’s wonderful …”

In many ways, the beating heart of Paterson’s work is not in any material outcome as much as it is in the relationships it forges. She says she’s using Chat GPT a lot at the moment, to just fire off questions and see what comes back. She opens the app and reads through her recent searches: “Newton’s colour music theory, future Pangean Mountains, recreating life's origins, how to grow crystals, marriage to landscape examples, cardinal points explained, bird sleep patterns, snow-camouflaged animals, cosmic time visualisation, Pliny on snow and ice, particle interactions across the universe, futuristic weather symbols, visual stars counts, Mars day length, mineral-rich rivers.”

“I’m just having fun and it's so interesting, but ultimately, it's only reminding me how necessary it is to sit in a room with somebody, or in a forest or under a snowy covered tree or whatever, and listen to actual opinions and things.”

She describes the exacting process of making The Moment, with lamp-worked glass specialist Ayako Tani at the National Glass Centre in Sunderland. For the hourglass to run for exactly 15 minutes, they had to grind down the cosmic dust in five different grades. Tani then had to get the aperture just right: “I think it was like three quarters of a millimetre that she had to achieve,” says Paterson. Each project involves “all these endless experiments, endless breakages, endless issues, endless headaches. And then eventually, when you get the thing, I'm always astonished that it actually works. At that point, I love it, because it feels like, even though it's the simplest thing, we have usually got there by way of some very unusual technique. And it's not just me that's happy. I love the feeling that everyone else seems to have got a lot out of it too, because they tend to like a challenge themselves, and to work with materials to their extreme.”

One of the most arresting items on her website is the essay-length archive of acknowledgments: 3,384 words, mostly names, listing all the people and institutions whom she has brought into the fold in order to realise the 40-odd Ideas she’s made happen to date. In this way, Paterson shares with the likes of Francis Alÿs and Christo a clarion ability to get people on board: to persuade them to do the completely unexpected.

“The first time I realised was making the phone line to the glacier,” she says, referencing one early piece, Vatnajökull (The Sound of), that she showed in her final MFA show. She’d written a mobile phone number, 07757001122, in neon-tube lighting on the wall. You could call from anywhere in the world, and listen to the sound of Iceland’s Vatnajökull glacier melting into the Jökulsárlón lagoon, by way of a submerged microphone.

“I'm such an introvert by nature,” she says, “but I kind of realised quite quickly that there's just no way that this was ever going to happen unless I sort of put a mask on and just tried to persuade people. I had to do that in the first meetings with Virgin Mobile, because they sponsored that piece. And not much has changed. I have to put aside the feelings of dread and focus on how wonderful it would be to do this thing.”

She says it helps that the people she’s approaching are usually wildly enthusiastic about whatever their specialism might be—black holes, DNA data encoding—and so can effectively resonate with the enthusiasm she’s communicating for her own singular purpose. Indeed, like a magnet, her out-there-ness prompts a similar daring in whomever’s working with her. The other day, she says, she was speaking with the director of a public library in the US about possibly doing something related to the Future Library there. And he said, “Well, we’ve found this room inside an arch in a park …”

“And so suddenly it looks like we're hopefully going to be doing something in this strange room, in the arch,” she says. “And now the architects are making suggestions. They’re talking about bringing in a tree …”

And she’s off to the races, the light of a thousand stars in her eyes.

Notes

*From the To Burn, Forest, Fire website: “The Earth’s first forest grew in modern-day Cairo, New York State, 385 million years ago. It was discovered through fossilised root systems containing three types of ancient plant species, including Archaeopteris, which had well-developed roots, a large trunk and branches with leaves. What would it have been like, this forest? A shady place of greens and browns, certainly, but probably with little other colour – the evolution of flowers was still a long way into the future. A quiet place, probably – not quite bereft of animal life, for small millipedes, mites, springtails, crustaceans and other invertebrates had already moved onto land with the plants.”

“The second incense stick recreates the scent of a living forest biome that is acutely endangered, and has become an emblem of the ongoing ecological crisis: the Amazon Rainforest. Home to about 10% of all biological species on Earth, the Amazon has thus far been deforested by about 20%. Reduced rainfall due to climate change is driving a feedback loop in the Amazon involving wildfires and the local hydrological cycle, which could convert much of the rainforest to savanna by the end of this century.”

“In To Burn, Forest, Fire, the Amazon is represented by a single locality: the Tiputini Biodiversity Station in the Yasuní Biosphere Reserve in Ecuador. The Tiputini station provides the IHME commission a discrete look into the Amazon which, at least for the time being, remains a vast and varied rainforest biome.”

**I love this list: “Al Khatim Desert, Albuquerque Basin, Alvord Desert, Antarctic Polar Desert, Arabian Desert, Aral Karakum, Arctic Polar Desert, Atacama Desert, Black Desert, Chalbi Desert, Chihuahuan Desert, Coral Pink Sand Dunes, Death Valley, Deliblato Sands, Gibson Desert, Gobi Desert, Great Basin Desert, Great Rann of Kutch, Great Salt Lake Desert, Great Sand Sea, Great Sandy Desert, Great Victoria Desert, Guban Desert, Indus Valley Desert, Islands becoming desertified, Jalapão, Judaean Desert, Kalahari Desert, Karakum Desert, Katpana Desert, Kharan Desert, Kyzylkum Desert, La Guajira Desert, Little Sandy Desert, Locharbriggs Sandstone Formation, Lompoul Desert, Marine Desert: Baltic Sea Dead Zones, Mojave Desert, Monegros Desert, Navajo Sandstone, Ndioum, Nyiri Desert, Oceanic Desert Islands, Oltenian Sahara, Ordos Desert, Patagonian Desert, Pumice Desert, Red Desert, Sahara Desert, Sechura Desert, Simpson Desert, Sonoran Desert, Sprengisandur, Tennger Sand Sea, Thal Desert, Thar Desert, The Cyclades, The Empty Quarter, The Ka’ū Desert, The Namib, The Negev, The Richtersveld, The Sinai, The Syrian Desert, Uyuni Salt Flat, Viana Desert, Wadi Araba, Wadi Rum, White Desert, and White Sands”

***Two more recent pieces riff on Mirage in new ways: Circe features dozens of thick 15cm-wide glass discs (coasters? trivets?), each made from a different batch of wild sands and arranged by colour on a metal track on the floor: together they shade in an ombré of clear to apple to olive to aqua to teal to pearl. Spectre, meanwhile, is a single pane of glass, 54.6 x 36.8 x 2.5 cm, made in collaboration with the Studio of the Corning Museum of Glass, using sand from every desert on Earth.

Pull up a memory

I wrote about walking to the library every day this week and quite how Senate House has changed my working life. When I was little, I always looked for the oldest cloth-bound hardbacks. I figured that’s where the best stories lived. And now, they’re all around me. Here’s the book I randomly picked up for the photoshoot: a 1975 reprint of Guillermo de Podio's Ars Musicorum, from 1495, written in Latin and printed entirely in tight Gothic on high-density paper, with a spine label that looks like it hasn't been replaced since the book was new. Isn’t it a beauty?

Do you have a favourite library?

World of Echo

It’s 25 years since Yo La Tengo released And Then Nothing Turned Itself Inside-Out, so here it is, this absolute masterpiece. Enjoy how the suitably cosmic title resonates with a few of Paterson’s Ideas:

“The oldest object enclosed within the newest”

“The darkest place in the universe pierced”

“A city built from antimatter”

“A nightlight the colour of the end of time”

Listen to all 17:42 minutes of the last track, Night Falls on Hoboken, and tell me you didn’t just hear the sun set in real time, from last ray to tallest shadow. Also, how beautiful is that Gregory Crewdson cover photo?