More than air in the air: Portia Zvavahera's prayer-filled world

In Zvakazarurwa at Kettle's Yard, the Harare-based artist uses lace and foliage and bone-deep feeling to build images of protection and resistance

Today’s letter debuts my reviews section — I’m hoping I’ll get to the point where I can send you one a week, a deep-dive into one exhibition I’ve spent good time with. I’m publishing it in collaboration with

’s Shade Art Review. As always, let me know what you think.Do you ever pray? Do you ever feel more than air in the air, more than water in the water, even when you’re only washing dishes? Can you lie in bed at night and project your soul into the light and shadow playing on the ceiling? Do you hear more than song in singing? Do you sing with other singers?

In collaboration with the Fruitmarket, Kettle's Yard in Cambridge has just opened Portia Zvavahera’s solo show*, titled Zvakazarurwa, which in ChiShona translates to “revelations”**.

The exhibition is divided into two sections, with an additional work in Jim Ede’s house itself***, a single almost square-format oil painting titled Fighting Energies 2, from 2024, installed on a high wall above the double-height salon.

In the first room, you have a selection of works from the early 2010s onwards. In the second, a newer series based on a single dream. Together they present an elegant exploration of layered vision — where being in the world is as much a spiritual experience as it is, an embodied one.

Running through all 22 works is this interplay between container and barrier, threat and protection, things hoped for and the stresses to hold them together, between embracing and warding off, between kneeling down and flinging open.

What’s interesting to note is the echo between the formal developments in the works of the two rooms (how Zvavahera makes her images) and the ideas that underpin them. If the earlier works show you a central protagonist’s world from the outside, the more recent works feel like you’re being brought into the fold.

In the first room, you have all-over paintings, where the canvas is entirely covered and the image it depicts is constrained only by the limits of the stretcher. They’re like cutouts or snapshots of a world unfolding.

Labour Ward, from 2012 (at the top of the page), proffers a tight crop on three pregnant women lying on parallel metal-framed beds. Their contours, rounded and angular, punctuate the space of the ward in a musical sequence, a kind of expectant polyphony.

Quite what those sounds might be is brought home more emphatically with the small, neighbouring canvas, Labour Pains, also from 2012. Here, a single travailing woman is seen from above, at an angle, the shape of the bed beneath her foreshortened into a kind of Matisse-like armchair. All the focus is pushed towards her, this mother in the actual making, a sequence of rounds at work with eyes like pools, a mouth open in blue shadow, her hair hanging down in echo of her long fingers.

I love how Zvavahera paints human figures. The expediency of her gestures, the minimal marks. Here’s a hand, here is a look, she’s saying, here is something very real that you know very well if you let yourself feel.

Embraced and Protected in You from 2016 is altogether more abstracted but no less filled with presence. Stretching 4 meters wide, it layers three figures in a composition that too feels musical.

These women are leaning back, hands splayed, heads thrown back, chins lifted, absolutely giant feet. The largest is in the background, all in white, an expanding mass of wafting florals with hands bigger than her head, holding the other two in a bodily embrace that fills the canvas.

In the videoed interview at the entrance to the show, Zvavahera describes how when she was little she dreamed of having a white wedding dress and then how that lace morphed into a kind of angelic protection. You see that motif shapeshifting from painting to painting, here a veil, there a wing, there a curtain or a shroud or a tent. Fabric — as cocoon and shelter both — is everywhere.

The works in the second room are all essentially riffs on a single dream, or nightmare, Zvavahera had while pregnant. The main, monumental work, Pane rima rakakomba (There’s too much darkness) from 2023 relays what she dreamt. A central figure lies on her back under the maroon-coloured shade of a tree. Another winged figure kneels at her head, a distended arm reaching, cradle-like, around her. The interplay between their two faces is remarkably tender. With just a few marks, Zvavahera conjures the depth of a Käthe Kollwitz, or one of Frank Auerbach’s charcoal heads.

A ways off, several others, in brighter colours, gather at her side, while purple-coloured rat-like shapes with long tails descend from above, to encroach on her space. The scene, almost entirely overlaid with quickly sketched foliage patterning, does not fill the canvas. Blank margins reveal where the painting has stopped, isolating the image from its surrounds, like an island. Zvavahera talks of doing so because she needs God to fill and complete things.

To my mind, it’s as if we’re now inside the interiority of the earlier works. That isolated inner space where fear and joy and resolution and anguish and prayer, if we pray, are born.

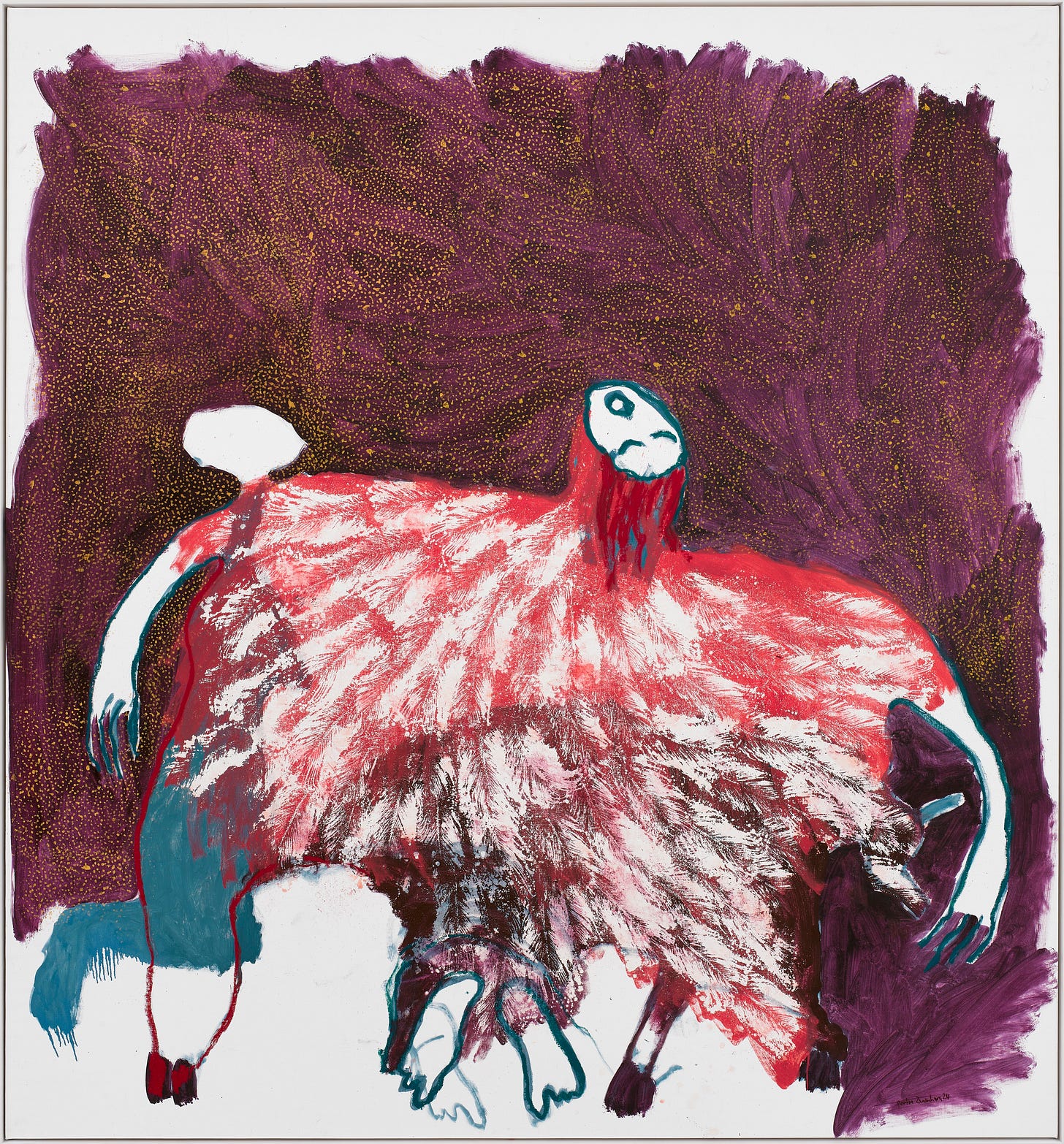

These works form a coherent whole, with a reduced colour palette on a white canvas background. There are lines drawn around shapes, reminiscent of the shapes of the women depicted earlier. Figures are reduced to head and stretched out arms. Sometimes the over-extended chest in between becomes a feathered or patterned haven. At others, the embrace is a barrier to contain the rats. Often, seemingly abstract expanses or shapes culminate in a pair of feet, of which you only see the upturned souls — those of someone kneeling in bare feet.

Zvavahera’s works make family and the urge to hold it close so very tangible. To gather and to guard. On one’s own, in community or in communion.

Portia Zvavahera: Zvakazarurwa is at Kettle's Yard, Cambridge until 16 February 2025 and will then travel to The Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh, from 1 March – 1 June 2025.

Notes

*This is Zvavahera’s first institutional solo exhibition in Europe, a fact the two gallery directors, Fiona Bradley and Andrew Nairne, rightly point out is absurd. Zvavahera has been prominent on the international art scene for over a decade. She was part of the Milk of Dreams exhibition at 2022 Biennale di Venezia, curated by Cecilia Alemani and she represented Zimbabwe at the 55th biennale in 2013.

**The catalogue contains a transcribed conversation between the curator Tamar Garb, writer and director of Stevenson Gallery Sinazo Chiya, Tandazani Dhlakama, who is curator at Zeitz MOCAA, and Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela, the professor and research chair in studies in historical trauma and transformation at Stellenbosch University.

I love this passage from Gobodo-Madikizela:

“When I started looking into [Portia Zvavahera's] work, for me, there was this palpable link to her dreams, but also to an archetypal set of references for her dreams that speaks to a much broader cultural context, experiences that extend beyond herself, and which have affected women in her community. As private as dreams are, there’s also something collective about them. I can’t help thinking of a sense of mourning together, of connecting with other women’s pain. Yes, the imagery might come from a specific dream, but it’s a dream that connects her to a much wider circle of others. Maybe that’s why she couldn’t dream in London, being away from her cultural-communal context. For, dreaming can be like a call and response. You are called in a dream to act upon something. It’s not just your story. You are called upon to speak to and on behalf of your community. You are ‘chosen’, in other words, to speak on behalf of others. That’s what I find really so inspiring and fascinating about Portia’s work – it brings us back to the meaning of dreams in a collective and culturally specific sense.

*** Kettle’s Yard is this magnificent house and contemporary art gallery in Cambridge. It was home to Jim Ede, a fabled curator, collector and convenor of great art. Artists exhibiting there are sometimes invited to show in the house itself, which is marvellously conserved exactly as in Ede’s day, down to the fresh lemon he always liked to have on a pewter serving dish, in echo of the yellow dot in Joan Miró’s Tic Tic on a nearby wall. That kind of resonance always makes going to see work at Kettle’s Yard exciting. I loved the connections between Zvavahera’s pieces and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska’s Wrestlers relief from 1913 and St. Edmund, the charred piece of willow wood John Catto found in 1975 and gave to Ede because he knew he would appreciate it.

the power in the bodies of these painted figures is amazing...beautiful review, thank you Dale