Some Tuesday treats #3

Tradition as speculative imagination, scaffolding as process, bubblewrap as spots of time, joy as resistance, admiration for the old painter from the north

A week of filmic disquiet. Gene Hackman died, alongside Betsy Arakawa, his wife of many years of whom I instantly thought, but we didn’t know you, not that “we” could have, but who were you. It made me so sad that every news piece described her as a concert pianist, yet when I looked for footage of her playing, I couldn’t find any. She’s forever an outline now, an absence with frozen hands.

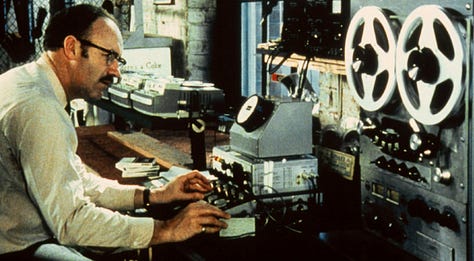

Coppola’s The Conversation (below left) is a movie that has stuck to my mind’s ears like glue along with several Wenderses—Der Himmel über Berlin (Wings of Desire)*; Lisbon Story (middle); Paris, Texas (specifically, the peep show; right)— Wong Kar Wai’s Happy Together (the scene where he whispers into the wall) and Sokurov’s Pages Cachés (Hidden Pages).

Then Daniel Blumberg won an Oscar for his indelible soundtrack for The Brutalist, a film that also has not let go of my insides for weeks and weeks. Very exciting was Blumberg’s shout-out to Café Oto, our collective second home, that Keiko and Hamish dreamed up while sharing a studio with Hiraki several lifetimes ago**. And the fact that Ute is one of the “radical, uncompromising” musicians Blumberg mentioned. Radical, uncompromising.

Here, then, a meander of sentences and images, along those lines, that have stuck in my head this week.

I found it so strange that architects took issue with The Brutalist’s architectural incongruities because, really, it’s only about architecture on the surface. It’s so arresting, so abrasive, so very old-school a filmic parable—about humiliation and power and oppression in the 20th century. Some critics brought out that favourite populist slight, “self-indulgent”, to describe sequences like the train speeding along, for quite some time, before its silent distant crash. But I’ll take any instance of the 21st-century big screen allowing a director some empty time, some seemingly dead air, some space, to just see what happens when you let an idea breathe.

In its marriage of profound disquiet and countryside grandeur, and that intense soundtrack, The Brutalist keeps making me think of Alain Resnais’s L’année dernière à Marienbad (see above).

I keep thinking about Zsófia, László's niece (below right) who is traumatised into silence / refuses to talk and how crazy that makes Joe Allen’s (ignorant, impatient, entitled, belittled, oppressive) character, Harry. Maybe she’s what has led me down a Joan of Arc rabbit hole — to the magnetism of Carl Theodor Dreyer’s 1928 silent The Passion of Joan of Arc (left) and to Robert Bresson’s 1961 Procès de Jeanne d'Arc (middle).

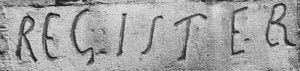

“Register” > “résister” > “resist”: the inscription you can read carved by many hands into the stone of the Tour de Constance in Aigues-Morte, the 13th-century tower on the Rhône delta in the Camargue, where in the 18th century, Protestant women were locked up — entombed, really — because of their faith. Many died there. Several pregnant when they were arrested and brought up their children there, with scant resources, illness, rats, madness.

The carving is often attributed to Marie Durand, who was imprisoned in 1730, aged 18 and only left the tower 38 years later, in 1768. André Chamson tells this story in his 1970 book, La Tour de Constance, which I read at Christmas. Still can’t stop thinking, beyond the obvious dire lack of food and cleanliness and not being able to walk, about having periods and giving birth under such conditions.

The Steve McQueen-curated show at Turner Margate, Resistance: How protest shaped Britain and photography shaped protest. Of the many emotions triggered, I was overwhelmed by all the women fighting for their right to be safe, oftentimes with children, or for children, or reckoning with the loss of children. (Remind me to tell you next time about Shabna Begum’s incredible research into the Bengali Squatters Movement in 1970s East London.)

Below left: A covert photograph taken of a weary Christabel Pankhurst, pregnant Flora Drummond and Emmeline Pankhurst leaning on the dock, at their Bow Street Magistrates' Court sentencing in October 1908.

Middle: Julian Stapleton’s documentation of the 1982 vigil on the first anniversary of the New Cross house fire, that killed 13 children.

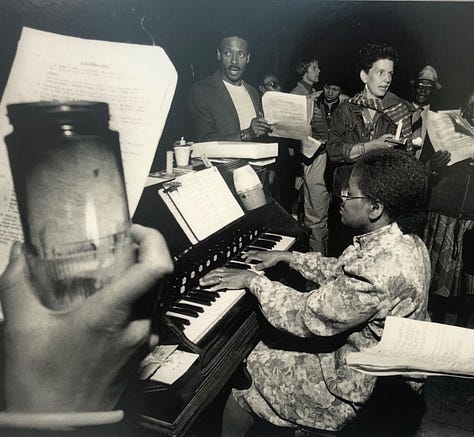

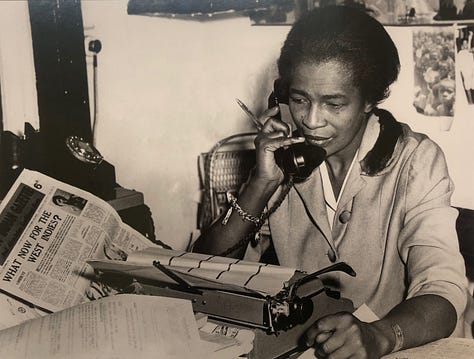

Right: Claudia Jones, in 1962 (photographer unknown), three years after she organised the first Caribbean Carnival at St Pancras Town Hall, in response to racist violence. “As founder of the West Indian Gazette, Jones understood that joy could be a form of resistance.”

Shabaka the Magnificent Hutchings, thinking about music in his childhood (click and listen):

“Mostly it’s the beats of soca and dancehall tunes I heard growing up in Barbados, before all the melodys and harmonic details are added, the foundations of the production. I also remember folk songs I was introduced to in primary school. I recall on my first day at Wesley hall, children dancing in a circle singing the chorus of ‘John belly mama’. That melody has stayed with me 35 years later. So for my solo set at black rock books it was a pleasure to explore cutting up the breaks of various calypso and soca tunes then juxtaposing older folk songs alongside them. Tradition as speculative imagination.”

Author Walter Murch on how the editor on a film observes its actors’ every move—“we inhale their rhythms”— and on working with Hackman on The Conversation: “In a very real sense, the integrity of Hackman’s performance provided the metronomic spine which supported and guided me, often without my knowing it, to find the correct pacing for each scene, and then the right structure of the collection of those scenes in the finished film.”

I’m writing about Michael Ajerman’s work rn, ahead of his forthcoming exhibition about which I’ll tell you more soon. During a recent studio visit, we spoke about small-size paintings, and he reminded me of the real Giorgio Morandi on the wall in the party scene in Fellini’s La Dolce Vita …

…which brought me to this excellent piece with the lovely detail that “Fellini was not alone in his reverence for Morandi. Some of the greatest directors of post-war Italian cinema—Antonioni, Pasolini, Visconti—expressed their admiration for the old painter from the north. He was, said Bernardo Bertolucci, ‘someone you could fall in love with.’”

And you really can, can’t you:

Morandi essentially just rearranged bottles and jars on a table, for decades, and drew and painted them. I couldn’t love his work more. I keep thinking about process v artwork, idea v object, and Jeff Wall going full countercultural in telling me the other day that, really, “I'm not a big believer in process. People think the process is so important. I think that's a little sentimental, because what we really want is the result. When I'm in process of making, it's very important, I'm trying to be very aware of it, because your mind is sending you warnings all the time about what you should and shouldn't do. But as soon as it's over, I'm done with that process. I don't have any interest in it anymore.”

Enjoyed, therefore, this piece about A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius by Dave Eggers turning 25, and the idea of process as scaffolding:

“‘Does there seem to be more meaning in these asides, footnotes, marginalia?’ [Eggers] once wrote in McSweeney’s. ‘Could it be that a group of writers, of a certain … age, feels more comfortable here, in the crevices, speaking their minds in these small, almost hidden ways, afraid to simply say things in plain language and bold type?’ Or, as he put it in one of the ‘removed passages’ of the book that he nonetheless found a way to insert back into the front matter: ‘See, I like the scaffolding. I like the scaffolding as much as I like the building. Especially if that scaffolding is beautiful, in its way.’” (Also, Axelle Ponsonnet’s documenting Notre-Dame’s actual scaffolding, for its beauty.)

This review of When It Rained for a Million Years by poet Paul Farley: “Whether asking the bank for an overdraft or losing a wedding ring, buying a new computer or reading the small print on a tin of peaches, the speaker has a gift for making the mundane seem magical. Even his ode to bubble wrap is far from banal – each plastic air pocket becomes a perspective-shattering pause. He calls them “spots of time” after William Wordsworth, who wrote about the small but significant moments that shape a human life. As each bubble is popped and pouf! it is gone, Farley reminds us of the brevity of existence, before the sharp distraction of fried bread draws us back down to earth.”

The visual and temporal rhythms of this earlier Paul Farley poem, Liverpool Disappears for a Billionth of a Second

Shorter than the blink inside a blink the National Grid will sometimes make, when you'll turn to a room and say: Was that just me? People sitting down for dinner don't feel their chairs taken away/put back again much faster that that trick with tablecloths. A train entering the Olive Mount cutting shudders, but not a single passenger complains when it pulls in almost on time. The birds feel it, though, and if you see starlings in shoal, seagulls abandoning cathedral ledges, or a mob of pigeons lifting from a square as at gunfire, be warned it may be happening, but then those sensitive to bat-squeak in the backs of necks, who claim to hear the distant roar of comets on the turn - these may well smile at a world restored, in one piece; though each place where mineral Liverpool goes wouldn't believe what hit it: all that sandstone out to sea or meshed into the quarters of Cologne. I've felt it a few times when I've gone home, if anything, more often now I'm old and the gaps between get shorter all the time.

Notes

*So many things I first encountered in French/France, it’s weird to say them out loud now in English.

** Such a fine line between radical experimentation and the actual Oscars.