#20 'This is not the only way to be. But it is the way that I am'

On balance and support, leaning on and leaning in, and wasting no time

A long time ago, I was in St James’s Park with Louisa (who I used to call Lulu On The Bridge, in homage to Paul Auster). I can’t remember if we were walking around or on the ground, but I do remember us both noticing a couple sitting in the grass nearby. For the longest time, they just leaned against each other, back to back, each in their own world, reading their own book. Then they turned around did the same, but front to front, like two hands clasping each other tight. Both arrangements were beautiful.

The image above is from Trisha Brown’s Leaning Duets, a dance piece she premiered on Wooster St in New York City on 18 April, 1970 — footage of the piece is in the MoMA collection. In Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue, 1961-2001, Roland Aeschlimann quotes Brown describing the piece as follows:

“Five couples, feet together, side of foot touching partner’s, leaning out to arm’s length, maintaining straight posture. Partners choose a direction, walking in that direction, touching side of foot together with each step. Fallen persons were hauled back up by partner while keeping foot contact. Rope device with handles also employed to achieve greater angle.”

I’ve been thinking about leaning and holding and pulling and what it means to lend support and what it means to play/compose/pose/harmonise/chime/pull away together and about balancing as a very active thing.

The Turner Prize shortlist was announced yesterday, which I’ve written about for Shade Art Review. I’m stoked to see included Nnena Kalu, who was featured in an episode, titled Mandala, of the 2022 Interludes podcast series by Shade Podcast, made in collaboration with sound producer Axel Kacoutié. The whole series is a wonderful enquiry into what healing might sound like – and this episode is particularly special. Kacoutié recorded the mesmerising, rhythmic sound of Kalu drawing her repetitive swirls in her studio.

Kalu is a limited verbal artist, and since 1999 has been in residence at ActionSpace, an organisation in London dedicated to supporting disabled artists. She worked in relative obscurity for some time but in recent years has shown her drawing and her sculpture – these woven, multicoloured cocoon-like shapes – consistently, at Manifesta 15 Barcelona, within the Whitworth’s recent Conversations show and beyond.

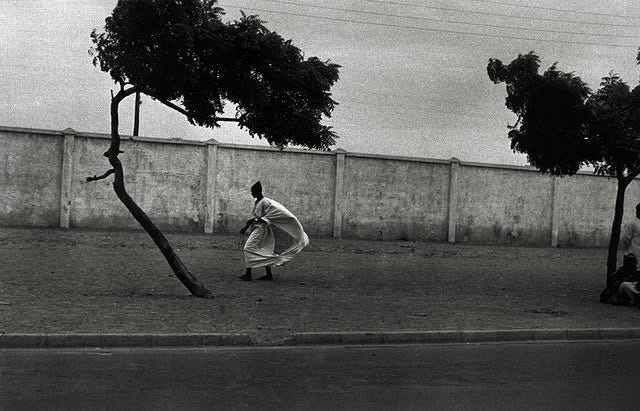

Another artist I love, whom Shade’s Lou Mensah featured in that series, is the US photographer Ming Smith, with her evocative compositions, these fleeting moments:

I’ve been watching The Residence on Netflix, in which Uzo Aduba plays, excellently, a detective called Cordelia Cupp. In one episode she tells her nephew, Ansel, about the first time she investigated a case, as a child. Her sister had lost a sock from her favourite pair. Cupp figured out it was the neighbour’s dog who’d stolen it. She’s telling Ansel this while she and he are on a camping trip by the ocean. Cupp is an avid bird watcher and she’s brought them to this beach in the hope of spotting one particular species. But it’s a testing time. The bird refuses to be seen. The boy is struggling to see the point. The sock anecdote becomes a way for Cupp to explain why she is the way she is. “I love your mom,” she says. “I didn’t like to see her cry and I told her I was going to find her strawberry sock and I did find it. That’s what I could do for your mom.

“This is not the only way to be. But it is the way that I am.”

Finding your rhythm. I keep thinking about how Ichiko Aoba described her process to me, in both the recording studio and on stage:

“I have to trust the moment. If I’m focused on this being my song, or that person being in the audience, or the light being too bright, or the sound feeding back when I play, it doesn’t work. But if I just let go, and truly believe that the music will be my protection, I can reach a state that is almost like meditation.”

I have always struggled to find that balance: between shutting the world out and letting it in, protecting what’s inside and only yours — so that you can make something worthwhile, something coherent and singular and tenacious and maybe beautiful but imperatively true and honest, something you can bear to gift the world outside in the hope that it could potentially/might hopefully help in some way — while also engaging with and caring for whatever needs caring for beyond yourself. Because so very much does. Aoba’s listeners say they find such solace in her work. “Fans say my concerts are safe spaces where they can forgive,” she said. And I thought, it’s quite something to be able to create any space at all, really, where someone else can feel safe, or seen, or loved, or at the very least, welcome. Where they can just breathe.

Here’s Arvo Pärt’s Fratres — “Brothers” — with a beautiful comment posted 10 years ago by @jafafa: “I'm going deaf, so I'm listening to this half from memory, I can't hear it all... but tears are streaming down.”

I loved this, from a rare interview Pärt gave in 2020, in which he talks about following John Updike, in following medieval sculptors “who carved church pews in places where it was impossible to see them”: the idea of dedication in the shadows, finding poise and reason and balance in one’s own heart, knowing why you do a thing and it not being about being seen (I don’t speak Spanish*, so have relied on Google Translate):

Pärt believes that ‘what's happening is forcing sacrifices on us all,’ like ‘a kind of mega-fast’ that has ‘its effects,’ a ‘deprivation’ that culture is not immune to. As a creator, the Estonian always strives—even now—to follow the example of writer John Updike, who ‘once said that he tried to work with the same calm as the masters of the Middle Ages, who carved church pews in places where it was impossible to see them.’**

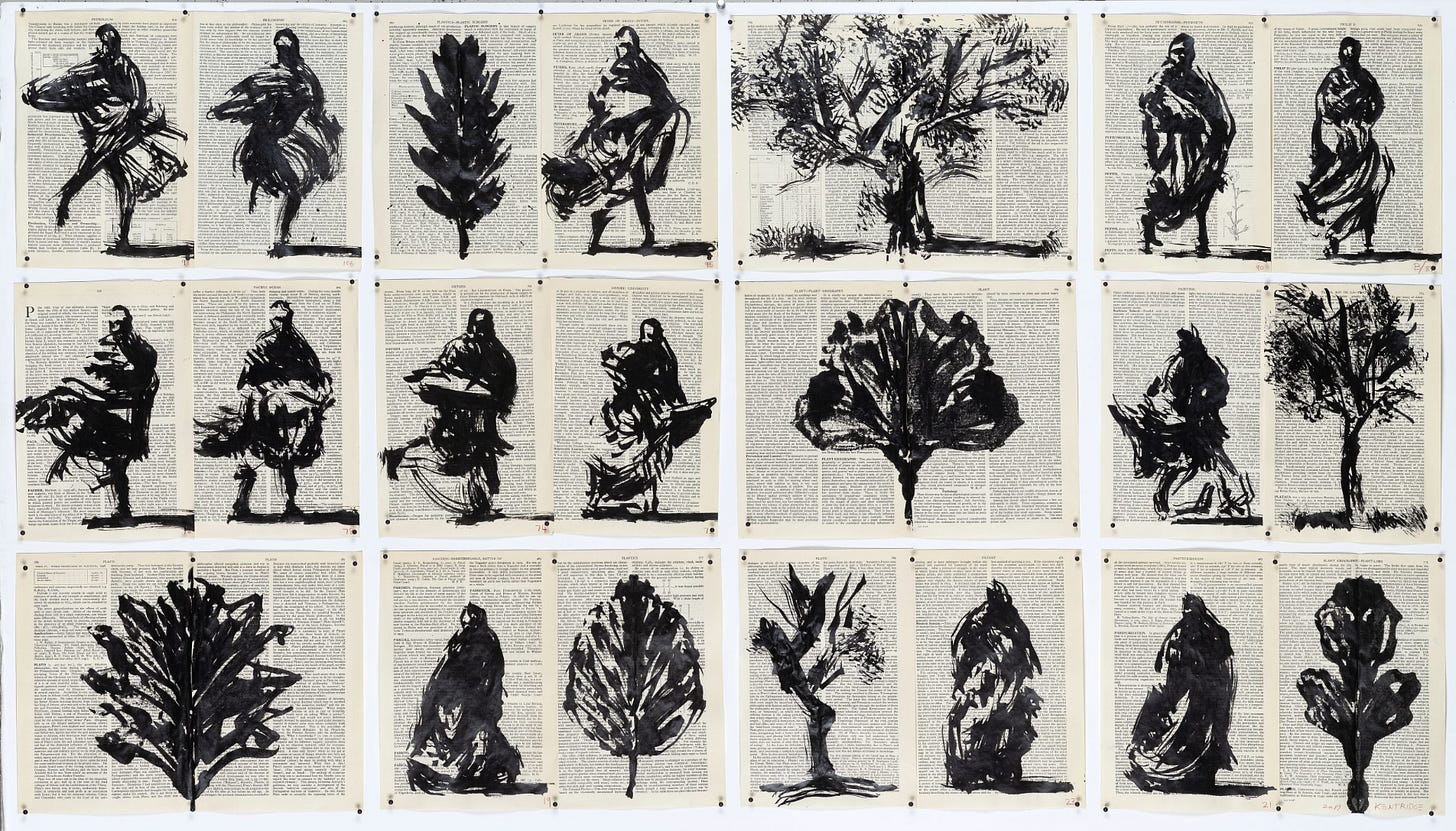

Another piece I’m always thinking of is William Kentridge’s Sibyl, a film based on his opera, Waiting for the Sibyl, from 2019. It’s a characteristic medley of song, dance, superlative set design, animation, writing and sound. When it was shown at the Royal Academy in 2022, I watched it repeatedly, and each time, got stuck on this bit in the middle of the film, accompanied by a magnificent song, by vocalists Nhlanhla Mahlangu, Xolisile Bongwana, Ayanda Nhlangothi, Zandile Hlatshwayo, Siphiwe Nkabinde and S’busiso Shozi. I can’t embed the film but scroll down, here, to the embedded clip titled Sibyl Flipbook film and fastforward to 1:55.

Forget the smell of eucalyptus leaves the smell of the wing (as it once was) Let them think I am a tree or the shadow of a tree A doubt a shadow of a doubt your days will become years your years will become places But no place will resist destruction The nearer inferno The greater paradiso Death grows its tree inside you Waste no time You have nowhere to go But joy will overtake fear

Also those drawings, of the dancer becoming a leaf and a tree.

And a track, titled Appalachian Excitation, that Arnold Dreyblatt did with Megafaun also a while ago. I’m always thinking of Dreyblatt, with his drones, those solid throughlines that act as something like contour lines on a map or hiking trail markers.

In 1968, US land artist Nancy Holt almost accidentally did a piece called Trail Markers: she and Robert Smithson, her husband, were driving through England and Wales on a recce for new sites for Smithson’s sculptures. Holt was driving. She started noticing orange dots in the landscape that were there as trail markers. As she told the art historian Joy Sleeman in 2013. “It's very hypnotic these little orange dots, and was interesting because they were very cleverly placed. Every time you got to a place where you might wonder where the next step might be there would be this orange dot. It's structurally interesting, and gave wonderful continuity to my slides. It was an artwork that evolved, came up, I didn't know I was going to be seeing it and then was seeing it and thought this was perfect. It was a gift. It was already there. My job was to get the perfect photo.”

Sleeman describes the piece as a kind of “found sculpture or readymade”, at a time when walking was taking on new significance in art and culture — she cited both Richard Long and the first Apollo moon landing, which happened just months later, on July 20, 1969. “On Dartmoor Holt encountered a place she found otherworldly but not entirely unfamiliar as it was somewhere she had visited imaginatively in stories from her childhood.” To Sleeman’s mind, Holt’s Trail Markers marks “a significant moment in the crystallization of a way of seeing the world”.***

Here, to send you off into your Thursday, is Yebba singing Evergreen:

Notes

*The original: “Pärt cree que «lo que está sucediendo nos impone sacrificios a todos», es como «una especie de mega ayuno» que tiene «sus efectos», una «privación» de la que no se libra la cultura. Como creador, el estonio procura seguir siempre –ahora también– el ejemplo del escritor John Updike , que «dijo una vez que intentaba trabajar con la misma calma que los maestros de la Edad Media , quienes tallaban los bancos de las iglesias en lugares donde era imposible verlos».”

**Note to self: watch Wim Wenders’s Perfect Days

World of Echo

Walking as a state of mind

***Along with this documentary taxonomy of the trail markers, Holt made her first buried poem, Buried Poem #1 (for Robert Smithson) – she wrote the poem, buried it, then gave Smithson detailed instructions on how to find it. Similarly, in Stone Ruin Tour, she recorded herself giving instructions on a walk through a garden, with a ruin, in Cedar Grove, New Jersey, then transcribed those instructions to give to friends as a guide. Which, I suppose, is how I’m thinking of these letters too. Walks with finds and a list of markers or instructions for my readers on how to make your way to them too.

loved reading about your path towards balance as I walk a similar one "knowing why you do a thing and it not being about being seen" struck a cord and to be mentioned in a piece that includes Cordelia Cupp is the biggest honour!