Michael Ajerman: 'I found my reason to keep doing this'

Working with the kind of unreliability and confusion only a feline can instigate got the London-based painter out of an existential crisis and unlocked a new direction

On Saturday Michael Ajerman invited me to do a talk with him (which you can watch below*) about the genesis of the new body of paintings he’s showing at SQFT:Space Gallery (on until 26 April), a small but perfectly formed space just north of my kid’s school, it turns out. We spoke about what it takes to keep making work when the world seems to be telling you not to, and why focusing on whatever is right in front of you is often a useful way to work. Also, about a cat – in all its unpredictability – is an excellent means through which to re-engage with drawing. Ajerman and I have been friends a long time. He studied at the Corcoran School of Art, the New York Studio School, the Yale Summer School and the Slade School of Art, which is where we met. His knowledge of art history is encyclopaedic. He’s got great taste in music (Spotify playlist below as well**). Of his work, I’ve always loved the twistyness, the spikyness, the exhilaration, the verve — the humour! Mostly, I love how he paints. I visited him in his studio in North London ahead of the show and wrote a text for him. Here it is, with added detail from our interview.

Michael Ajerman once had a gallerist bemoan the frenzy of his works. “Your paintings are so energetic,” they said, “we can't put anyone else's work next to yours.”

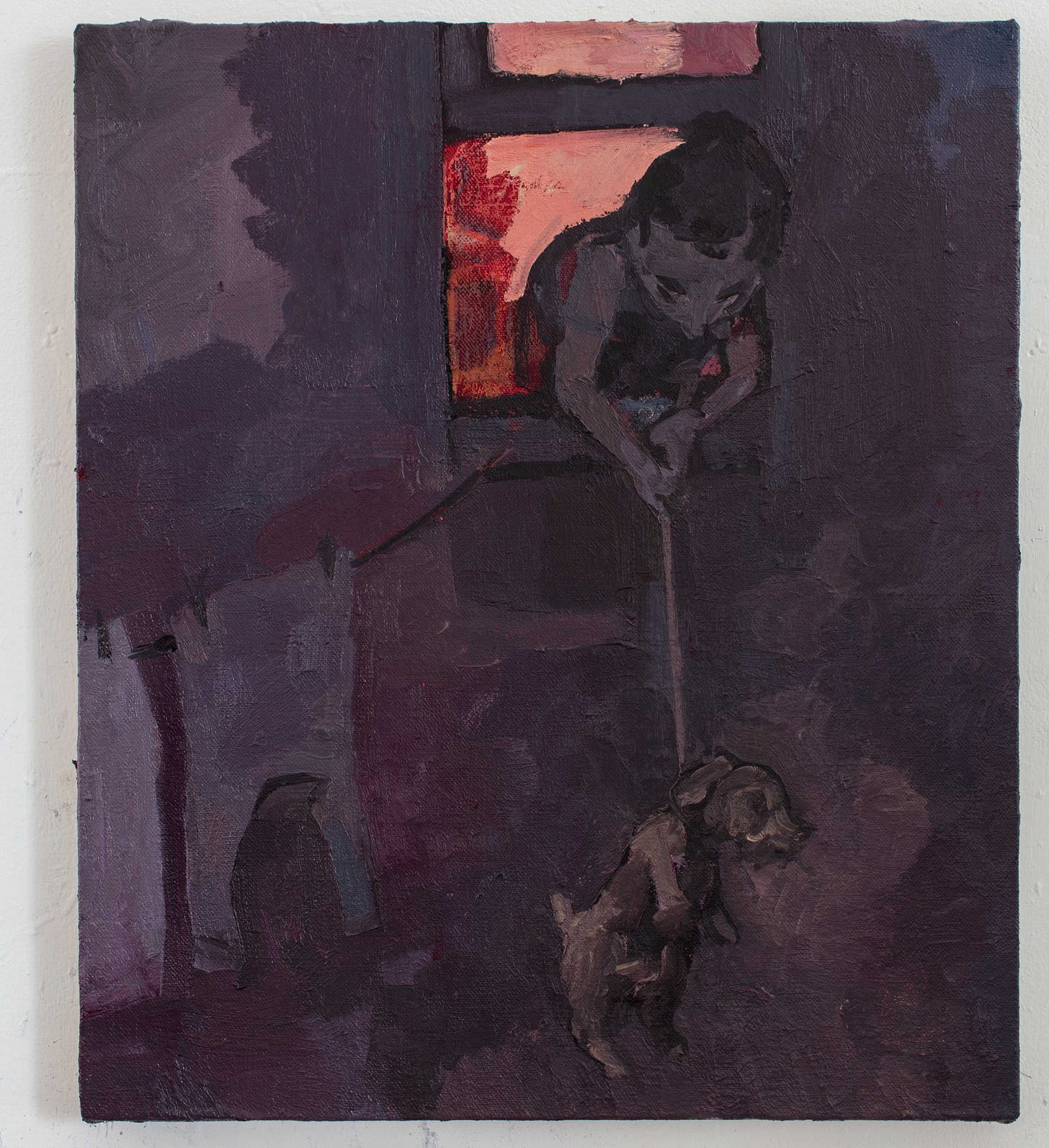

The absurdity of that objection notwithstanding, if you did need to choose one word to encapsulate what Ajerman does, like a knot of colour in a glass marble, it would be spiky. Figures and shapes and lines and forces rail against the strictures of any given canvas, suggesting noise and restless muscle, an ever-threatened containment, an explosion inches from exploding.

A few years ago, there was a war on his Camden street. He and his partner, Laura, had gone out for lunch then walked home. Within 20 minutes a roar had them back outside, watching two cats—Grendel and Couscous—going at each other with ferocious intent. “They were flipping each other in the street. One of the guys from the street, who's the son of a screenwriter, is like, ‘I know that cat. That cat cost me 3000 pounds in vet bills. Is that cat yours?’” Ajerman didn’t know what to say. As he puts it, Grendel “has lots of homes”. It's a strange existence, he says: you care for something, but it's really out of your control.

Ajerman has come back to that Fight-Club-meets-Attenborough moment repeatedly ever since, mostly because, as he puts it, Grendel has brought him back to painting. See Almost, a rectangle divided on the diagonal across which twisting felines become crow or banshee.

A combination of Covid and bone-deep grief at the loss of a close friend sent Ajerman spiralling into a kind of existential crisis, where the reason for painting at all was lost to the chaos of the world. “A kind of Joan Didion crisis, like, what's writing for? And mine was like, What's painting for? I was like, my buddy is gone. I don't know if I want to do this anymore, I really don't know if I want to do this anymore. And then the whole world shut down.”

He points to one drawing, which, from this side of his most recent body of work now on show, looks like a new beginning. At the time only underscored his hopelessness. He'd drawn, unusually for him, inspiration from a news story. In the early days of lockdown, an Italian woman had been videoed dangling her dog by a long leash from a first-story window, so it could do its business while she wasn't allowed outside.

It was a defiant gesture. And, as images go, a kind of madness. As such it presages the direction in which drawing and painting Grendel has taken Ajerman's work since.

At first, he had no idea what he was trying to do. Cats will sit, lie, nap and pounce but for how long, no one knows. “The cat is, in a sense, quite adorable, but he's quite fierce, too, and, you know, it's not like having a lion in the living room, but there's times where you're kind of cautious of the thing.”

Working with that level of unreliability unlocked a kind of new direction. He thought about David Hockney's Dog Days: “I had recently had read that he was doing all those when he was having this huge crisis, when all his friends were getting ill and dying, and there weren't that many social gatherings. So he kind of turned to what was closest to him.”

He thought of Bonnard's use of cats: “Were his cats always pictorial devices, or were they actual portraits of animals specifically?”

He sat with the muscularity of Egyptian cat sculptures. He also just sat with the cat’s own presence, trying to figure out how to capture it: “It's just a kind of a movement and energy in paint. Can I relate it to him? How do I relate it to him?”

Ajerman knows the history of painting like the back of his hand. But that doesn’t mean he likes a lot of it. Certain artists, though, he speaks about the moment he discovered their work as finding something he needed. First, the Austrian artist Maria Lassnig's radical self-portraiture, and her theory of Körpergefühl: body awareness.

Then the physicality of Kazuo Shiraga's practice—the unresolved spaces inside his marks. Shiraga was a Japanese painter associated with the Gutai Art Association movement (alongside Atsuko Tanaka, about whom I’ve written before). He found a way into radical abstraction through painting with his feet, resulting in what Ajerman describes as “these kind of long battles, big kind of swirls of colour, knocking and bashing into each other.” As with Lassnig’s work, he says, in Shiraga’s there was something he found that he had been looking for.

And then there’s Frank Auerbach, for whom we share a great love. Ajerman clocked the dogwalkers Auerbach recorded on early morning walks on Primrose Hill (“because if he was insomniac and up at 6am, that’s what going to be on Primrose Hill, it’s going to be people walking their dogs.”) and the altogether more sedate cats he included in two domestic scenes: Stella West with her daughters and Julia with Jake at the table.

An anecdote about the French artist Balthus reportedly living later in life with 40 cats in the South of France, meanwhile, suggested the image of a painter napping under a pile of furballs. “ I had this image of someone taking a nap from work, or from the studio, or whatever, and just basically being drowned in cats.”

I love how the Reposto series, below, kind of workshops this idea of the artist as a mad cat lady. It’s about piling on, a flurry, a furry frenzy, a messy mass. It’s also about having more than one figure in a frame – something the painter Timothy Hyman, with whom Ajerman says he had “a kind of slightly punchy friendship”, always asked him about. “When are you gonna have more figures in your pictures?” he’d ask.

The body of work that has resulted from this collaboration with Grendel are a kind of wild playbook. They’re all pretty small canvases but they’re all kind of creaking at the edges, just barely containing this electric lifeform. They’re live-wire alive. Oscar's Levitation, comic-like in its bounce and shriek; Hunters and Prancer, both riffing on the surefooted intent any cat demonstrates when they're on a curbside mission.

Everywhere, Ajerman deploys the kind of jagged summary gestural marks Auerbach so often uses to capture the essence of a dynamic shape in a landscape or a face. Even when they're not attempting to distill movement, Ajerman's new works vibrate.

Someone recently asked Ajerman if he still likes “doing this”, that is, making work. “Yeah," he replied, "I kinda like it more now. I literally laugh in here, either because it's not going well, or because something really exciting happens, or something happens in the picture.”

“I don't know if there'll be another crisis or something along the way,” he says. “I don't know. But, I found my reason to keep doing this.”

Painting as the sound of something happening.

Notes

*Here’s the IG live of the talk:

World of Echo

Emahoy (who I wrote about here) is first on Michael’s playlist, and Ezra Furman (who I wrote about here) is in the mix too – you can see why we’re friends.

Also, he wanted to end with what he called “an epilogue of sound”, that isn’t on Spotify: